Movies

Birdman (or, the unexpected virtue of the Academy Awards)

Birdman won the Best Picture Oscar at last night’s Academy Awards ceremony, something I predicted partly because it’s a movie about making movies, a subject of which Hollywood never tires. The fact that it’s also about the artistic ego – and how pride goes before the fall – could be seen either as the icing on the cake or the definition of Hollywood hypocrisy.

With the somewhat pretentious subtitle “The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance,” Birdman centers on Riggan Thomson (Michael Keaton), the former star of a staggeringly successful superhero movie franchise. Now largely forgotten, Riggan tries to reclaim the spotlight by directing and starring in a Raymond Carver adaptation on Broadway, which goes disastrously awry.

Birdman’s observations about ego and ambition are mostly on the surface. I enjoyed it more for its unhinged lead performance (Keaton was nominated but lost to Eddie Redmayne); percussive score; and breathless cinematography, which was structured so as to appear as if the movie consisted of one long, unbroken take (Emmanuel Lubezki won the cinematography award for the second year in a row).

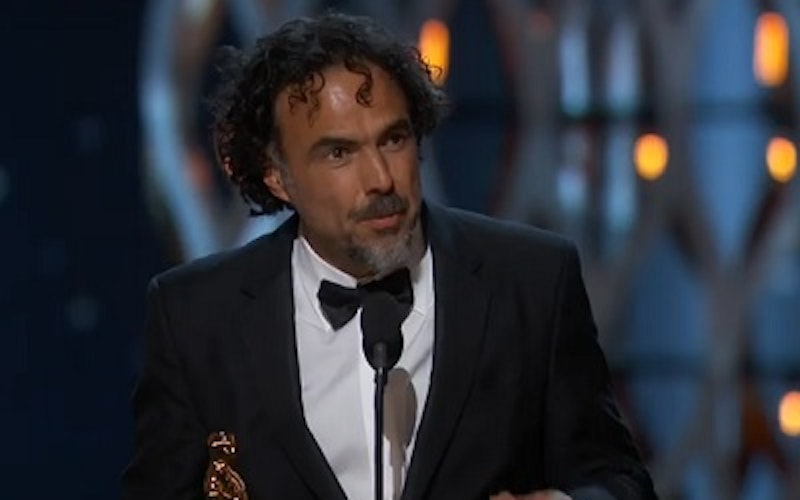

In his Oscars acceptance speech after winning Best Director, Birdman’s Alejandro González Iñárritu addressed the subject of his film, which he described as “that little prick called ego.” Speaking in his second language (he hails from Mexico), Iñárritu said:

Ego loves competition. For someone to win, someone has to lose. But the paradox is true art, true individual expression, as all the work of these incredible fellow filmmakers can’t be compared, can’t be labeled, can’t be defeated. Because they exist and our work will only be judged, as always, by time.

Iñárritu’s words, especially his reference to competition, recall C.S. Lewis’ thoughts on pride, which he identified in Mere Christianity as “the essential vice … the complete anti-God state of mind.” Lewis wrote:

The point is that each person’s pride is in competition with everyone else’s pride. It is because I wanted to be the big noise at the party that I am so annoyed at someone else being the big noise. Two of a trade never agree. Now what you want to get clear is that Pride is essentially competitive – is competitive by its very nature – while the other vices are competitive only, so to speak, by accident. Pride gets no pleasure out of having something, only out of having more of it than the next man.

Now, is Iñárritu really echoing these thoughts, considering he had just won a competition against the next four men on a night designed to separate Hollywood’s winners from its losers? Those critics who were suspicious of Birdman would say not. And certainly the fawning thanking of cast and crew and agents and family that Oscar winners do is part of the expected routine. Yet what if we were to take him at his word?

Then I at least find the parallels between Iñárritu’s thoughts and Lewis’ comforting. Both speak to an egalitarian ideal, one which sets aside ego while still allowing room for individuality. And while Iñárritu still seems to be working within a paradigm that includes eventual judgment – for him, it’s not his industry peers, but “time” - Christians can take comfort in knowing that Christ has removed judgment from the equation once and for all.

Topics: Movies, TV, Culture At Large, Arts & Leisure, Entertainment