Movies

Calvary’s portrait of a priest

“That’s nonsense.”

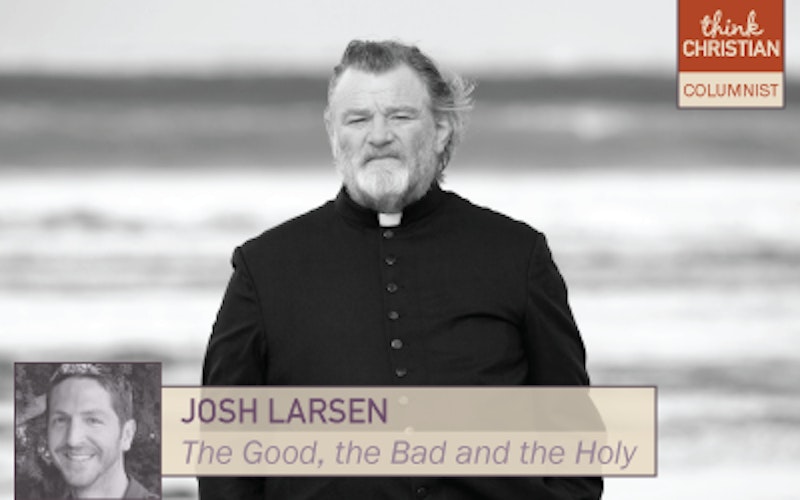

Not the sort of words you’d expect to hear from a priest, yet this is the most common phrase uttered by Calvary’s Father James. Played by the wonderfully belligerent Brendan Gleeson, Father James is a man in black, yes, but mostly in the manner of Johnny Cash: plainspoken and religiously rooted, with a clear eye for both salvation and sin.

Calvary opens in a confessional booth, where Father James hears what he himself describes as a “startling opening line.” A parishioner reveals the sexual abuse he suffered at the hands of another priest as a child, then tells Father James that he plans to kill him in a week’s time in order to punish the church. The rest of the film follows Father James making his usual rounds about the Irish coastal parish he serves, trying to decide if he should report the threat to police or offer himself up as a sacrifice to atone for the church’s sins.

Gleeson’s performance is the bedrock of the film. The volatility he brings to so many of his roles lies just under the surface here, as Father James endures the playful disdain of his largely skeptical parishioners, many of whom enjoying flaunting their sins in his face (bringing to mind Robert Bresson’s masterful Diary of a Country Priest). Father James calls them out on their “nonsense,” yet never wields the whip of condemnation. As he says at one point, “God is great. The limits of His mercy have not been set.”

Father James not only knows what grace and forgiveness mean in an intellectual sense, he also aches for them in his own life.

Earlier on TC, Todd Hertz wrote about the “the five pastors you’ll meet in Hollywood.” Father James would certainly fit in the “faithful” category, yet Calvary is no Pollyannaish paean to organized religion. There’s that opening confession/accusation, for one thing. In addition, Father James makes the doctrinally challenging observation that “there’s too much talk about sins, to be honest, and not enough talk about virtues.” Having come to ministry later in life – he took his oath after the death of his wife, a decision that’s caused tension with his grown daughter – Father James not only knows what grace and forgiveness mean in an intellectual sense, he also aches for them in his own life.

As such, Father James does not play the role of moral policeman. Nor does he serve as an evangelist. Instead, he mostly embodies what James Davison Hunter has described as “faithful presence.” In his convictions and his vocation, Father James hopes to offer a bit of God’s peace in the world. He is, above all else, there - available to listen to the imprisoned murderer grappling with his crimes and the unscrupulous investment banker who asks, “I feel like I ought to feel guilty. Is that the same thing?” Father James doesn’t approve of the sins he faces, but neither does he denounce the people who have committed them. He's simply there to hear their confession when they can no longer abide those sins themselves.

Topics: Movies