Music

Captain America, Spider-Man and sympathy for the villains

We love to see ourselves in our superheroes.

With the likes of Captain America: The Winter Soldier and The Amazing Spider-Man 2 in theaters, superhero season is in full swing. And while it’s natural to identify with the main character of most movies, this tendency gets amped up in comic-book adaptations. We all want to be the hero; something like Captain America lets us imagine what that might be like on a grand scale.

There’s even a theological impulse behind this. Most superheroes, after all, are fallen figures who arise despite – and often because of – their fallenness. Like us, they’re freaks – distorted versions of God’s creative intent. True, their freakishness is often the result of fantastic experiments (Captain America) or science-lab accidents (Spider-Man), but either way they - and we - are far from being creatures of Eden.

In this sense, though, aren’t we even more like comic-book villains? The heroes, for the most part, step up to the challenge, do the right thing and save the day (especially a straight arrow like Cap). The villains struggle greatly with their brokenness and are often consumed by it, which is a more accurate reflection of actual human experience.

Both Captain America: The Winter Soldier and The Amazing Spider-Man 2 provide examples of this. In fact, Captain America is the far better film partly for the way it handles its villains. The title character, the Winter Soldier, is a mysterious, metal-armed assassin who is revealed to have a connection to Captain America’s World War II past (the movie mostly takes place in the present day). How Cap (Chris Evans) responds to this revelation - I’ll only say his priority is not revenge, but restoration - gives the movie a relational richness that’s rare for the genre.

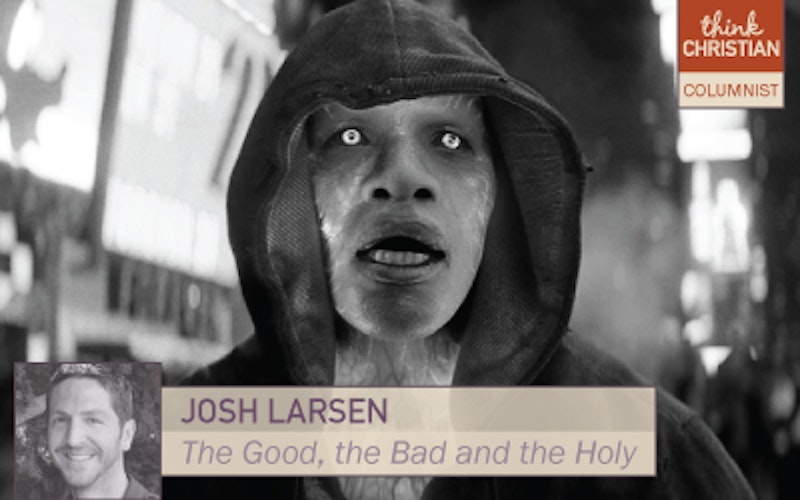

The populace Electro threatens can be saved by Spider-Man, but Electro himself is beyond redemption.

The Amazing Spider-Man 2 has a somewhat similar figure: Max Dillon (Jamie Foxx), a socially awkward electrical engineer whom Spider-Man (Andrew Garfield) saves from danger early in the film. Later, after Max suffers an accident at work, he develops powerful electrical abilities, calls himself Electro and for reasons the movie never quite makes clear goes on a destructive rampage. The Amazing Spider-Man 2 then follows the usual superhero trajectory, in which the villain - driven mad by his or her distorted identity - must be defeated. The populace Electro threatens can be saved by Spider-Man, but Electro himself is beyond redemption.

The Gospel, as is its wont, provides a more hopeful narrative. In The Cross of Christ, John Stott writes that “Christians can no longer think of themselves as ‘created and fallen,’ but rather as ‘created, fallen and redeemed.’” He goes on to say that becoming a Christian is a “transforming” experience, which means “that our mind, our character and our relationships are all being renewed. We are God’s children, Christ’s disciples and the Holy Spirit’s temple.”

At the same time, this hardly means we’re now heroic figures, with the good posture and noble intentions of Captain America. Rather, echoing Paul's hero-villain dialogue in Romans 7, Stott offers this caution:

There is, therefore, a great need for discernment in our self understanding. Who am I? What is my "self?" The answer is that I am Jekyll and Hyde, a mixed-up kid, having both dignity because I was created and have been re-created in the image of God, and depravity because I still have a fallen and rebellious nature. I am both noble and ignoble, beautiful and ugly, good and bad, upright and twisted, image and child of God, and yet sometimes yielding obsequious homage to the devil from whose clutches Christ has rescued me.

The thing I love about the reference to Jekyll and Hyde? He’s generally thought of as a villainous figure.

Topics: Movies, Culture At Large, Arts & Leisure