Music

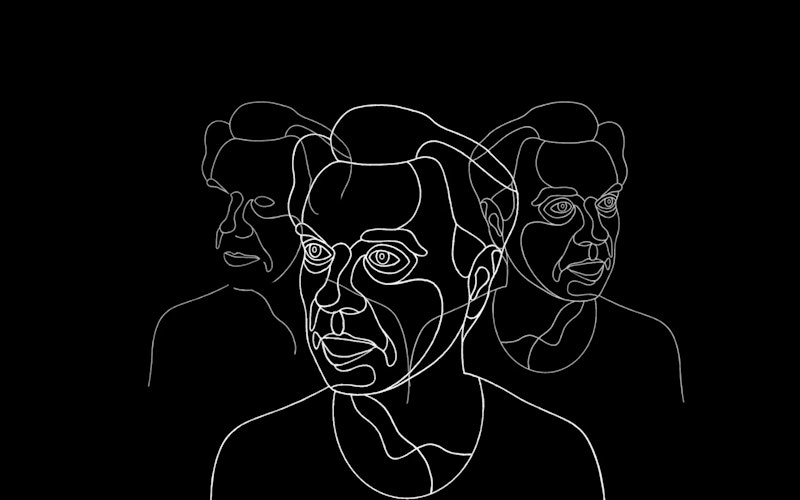

David Byrne Dreams of Utopia

David Byrne is going to prepare a place for us. And his house has many rooms.

That sentiment animates “Everybody’s Coming to My House,” the penultimate track on American Utopia, Byrne’s first proper solo record since 2004.

It comes near the end of a song cycle that searches for signs of life. On American Utopia, Byrne seeks the real, fleshy stuff of human existence and leaves no stone unturned or corner unswept. After taking stock and preaching sermons, he settles into a vision of collective flourishing: “Everybody’s coming to my house / I’m never gonna be alone / And they’re never gonna go back home.”

Byrne has always sounded like someone who dropped in from another dimension or was born in another world. The former head of Talking Heads conducts himself with the cool distance—and dance moves—of someone who doesn’t quite grasp the local customs. Yet his aloof manner grants him uncommon insight. Byrne sees through conventional wisdom and spots that which we can’t recognize or won’t admit about our behavior and need to belong.

This time around, though, he doesn’t sound like an explorer. On American Utopia he wants to stick around long enough to build something bigger than himself. But first he must determine whether this world really is inhabitable. His starting point is an ancient one. He names everything around him, appraising what should be cast away, what can be converted, and what is glorious as is.

“These songs don’t describe an imaginary or possibly impossible place but rather attempt to to depict the world we live in now,” Byrne wrote in a press release. “Many of us, I suspect, are not satisfied with that world—the world we have made for ourselves.”

The spirit of his searching hasn’t changed much since his Talking Heads days, but his questions have. Rather than ask “How did I get here?” or “My God, what have I done?” he poses a more forward-looking set of queries.

“Does it have to be like this? Is there another way?” he wrote. “These songs are about that looking and that asking.” It’s as if, by process of elimination, he’s leaving us a smaller, hopefully better set of answers.

“To be descriptive is also to be prescriptive, in a way,” he wrote. “The act of asking is a big step.”

On American Utopia, Byrne wants to build something bigger than himself.

Those big steps beg for equally daring musical leaps. Byrne takes risks throughout American Utopia, but doesn’t always stick the landing. “Bullet” is a prime example. Byrne bets the house on affected lyrical and musical constructions, reminiscent of a 19th-century art song, in an ill-fated attempt to bring a certain romance to the anatomy of a gunshot wound. At other times on the album, it sounds like he’s painted himself into a sonic corner in the late 1980s and early '90s. The cascading sitar which opens the otherwise solid “Gasoline and Dirty Sheets” feints toward the exotic in a way that Byrne has done before—and done better. The middling “Every Day is a Miracle” sounds like a Talking Heads b-side.

And yet, at his best, he seems to play a sort of pop music that has yet to be invented. This welcome shock is found along the serrated edge of “I Dance Like This” and in the bounding dance music of “Everybody’s Coming to My House.” “Doing the Right Thing” contains moments that sound like an ecstatic, ecumenical worship gathering where gospel, pop, and electronic strains collide and grope for the heavens.

Byrne’s diagnoses are an equally mixed bag of head-scratchers, knee-slappers, prophetic utterances, and non-sequiturs. He satirizes materialism on “Doing the Right Thing,” gently skewering people caught up in culture for culture’s sake. He calls for a return to something innocent, primal even, on “Every Day is a Miracle.” He imagines the good life and inspects our petty problems from a bird’s-eye view—in this case, the bird is a chicken. Sadly, “the pope don’t mean s**t to a dog” is as insightful as the lyric gets.

Byrne’s quest comes together on “Everybody’s Coming to My House,” one of the best songs of the young year. He describes a shared life that doesn’t quite match up to the standards of the early church, let alone the new heaven and new earth. But he’s looking for something similar.

Feeling alien in this life is natural. We look around us at forces as large as death, and as regular as disappointment, and know we must be made for something more. What we do with this inborn discontent is trickier. Even as he embraces a new vision, Byrne still sounds a little lost.

“We’re only tourists in this life / Only tourists but the view is nice,” he sings on the bridge of “Everybody’s Coming to My House.”

That squares with a biblical description of Christians as foreigners and strangers, exiles in this broken world. But where does that leave Byrne? Or us?

No dwelling place, no matter how great, or who you share it with, is complete without God’s presence. Every time he establishes a community or promises to form a new one, the point is clear: it’s so he would dwell among us.

Until we experience that in full, we’ll always feel like we’re standing outside a big front window with our faces pressed to the glass. Byrne can’t wrap his mind or music around the reasons his open invitation doesn’t produce an American Utopia. What’s missing is the realization that even if everybody you know shows up, only our welcoming God can make a house a home.

Topics: Music