Movies

Doctor Strange: Marvel Finally Makes Room for the Spiritual

Those looking for Christian orthodoxy in Doctor Strange will be sorely disappointed. Yet it would be a shame to dismiss the movie’s Eastern-influenced, occult-inflected spirituality too quickly. After all, this is the first film in the Marvel Cinematic Universe to allow that faith in something bigger than ourselves—rather than science, technology, or alien ability—can be a source of power.

When we first meet Dr. Stephen Strange (Benedict Cumberbatch), he’s a man who worships at the altar of science and reason. A brilliant, arrogant surgeon, his life is upended by a car crash that severely damages his hands. After a series of failed procedures, Strange is so desperate that he travels to Tibet in search of alternative medicine, eventually joining a secret society that practices the “mystic arts.”

Directed by Scott Derrickson, a Christian whose horror films (The Exorcism of Emily Rose, Sinister) have gained a following in faith circles, Doctor Strange can be seen as a witness to another world, one that cannot be explained by our technocratic age. Stephen Strange is not Tony Stark, whose engineering prowess led to the building of Iron Man; or Captain America, whose strength and longevity are the result of medical experimentation; or even Thor, who is—at the end of the day—a fallible alien. Strange is a disciple, a believer whose gifts come from a place he can’t fully explain.

Doctor Strange can be seen as a witness to another world.

Doctor Strange’s strength as a film is the way it visualizes this notion of spirituality. After much “study and practice” (a process that evokes religious devotion), Strange learns how to access other dimensions—including a Mirror Dimension that looks like our world, but is malleable for those who can conjure the proper spells. In one of the film’s most remarkable images, a church cathedral is unfolded from the inside by the movie’s villain (Mads Mikkelsen), one symbol of faith being contorted into another. In a different set piece, the Manhattan skyline is turned inside out like an inverted Rubik’s Cube. While fleeing from the villain’s henchmen, Strange runs up a skyscraper that has suddenly been turned sideways and later dodges a street that is folding in on itself. (The film’s special effects work owes much to Christopher Nolan’s Inception.)

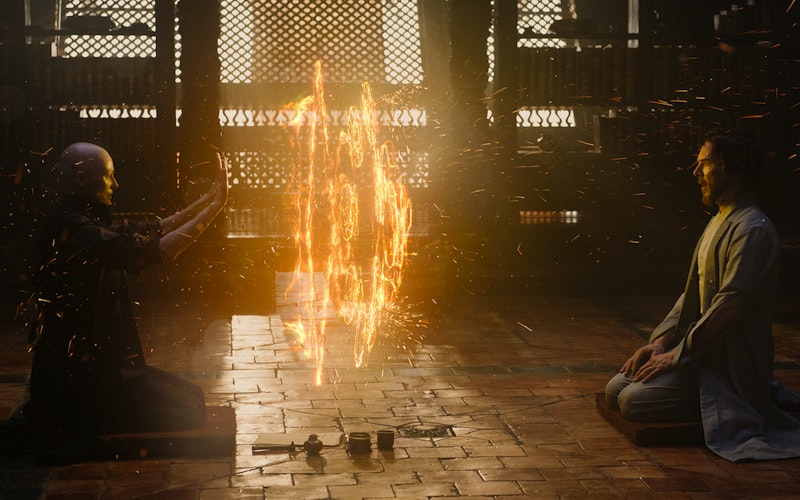

The portals that are opened to access the various dimensions in Doctor Strange look like circles of flame floating in the air, which the characters step through as if they were giant cats at a circus. Because this is an origin story, Strange is still a student of these mystic arts and therefore never quite sure where the portals he encounters (or even conjures) might lead. This brought to mind Paul’s words in 1 Corinthians 13, which dismisses what we know in favor of a new reality that, at least at this present moment, seems unclear:

Love never fails. But where there are prophecies, they will cease; where there are tongues, they will be stilled; where there is knowledge, it will pass away. For we know in part and we prophesy in part, but when completeness comes, what is in part disappears. When I was a child, I talked like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child. When I became a man, I put the ways of childhood behind me. For now we see only a reflection as in a mirror; then we shall see face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I am fully known.

In the Mirror Dimension of Doctor Strange, things are certainly refracted, often in unfathomable ways. “Forget everything you think you know,” Strange is told early in his training. In a Marvel universe that has heretofore heeded the siren call of secular humanism, as well as the attendant veneration of all things science and tech, this is strange advice indeed.

Topics: Movies, Culture At Large, Arts & Leisure