Movies

‘Give me the whip!’ Prop as Icon in the Indiana Jones Films

What would Indiana Jones be without his whip? It’s a question of character and theology.

We learn about the origins of the whip in the prologue for the third film in the series, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. There, before Harrison Ford reprises the role, River Phoenix plays a teen Indy on a mini-adventure that finds him falling through the roof of a circus train and landing face-to-face with a lion. Grabbing the whip hanging on the wall and snapping it at the beast—nicking his own chin in the process, thereby incorporating Ford’s signature scar—Indy buys himself enough time to be pulled up through the roof, via the whip, to safety.

It’s not the first time, nor will it be the last, that Indiana Jones’ famous strap transforms from a tool of violence to a life-saving artifact. Noticing this while recently revisiting the first four films in the series, in anticipation of Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, I began to wonder if that motif might hold a deeper resonance—if it might say something significant about Indiana Jones as a heroic figure. There are plenty of ripe theological themes in these films: the regular appearance of the divine; Indy’s deep skepticism of all things spiritual; his repeated invasion of sacred spaces, where he is inevitably humbled. Yet thinking about that whip, I kept returning to Isaiah 2:4. At his best, Indiana Jones turns swords into plowshares and spears into pruning hooks. Often, though not always, he wields his signature weapon to give life.

After decrying the rebelliousness of Judah and Jerusalem in Isaiah 1, the prophet offers a vision of hope in the following chapter. It’s a passage that provided comfort to God’s people in those ancient days, has soothed war-stricken believers ever since, and points ahead to the peace that is promised, with Christ, in the new creation: “He will judge between the nations and will settle disputes for many peoples. They will beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks. Nation will not take up sword against nation, nor will they train for war anymore.”

The Indiana Jones films take place during times of simmering conflict, from the lead-up to World War II to the early years of the Cold War. Amidst all of this saber-rattling exists a hero who is no pacifist (he carries a gun, after all, and frequently uses it), yet one who usually attempts to prioritize salvation over destruction. If Isaiah 2:4 suggests there is a better way of nation-building, might these movies suggest there is a better way of adventuring?

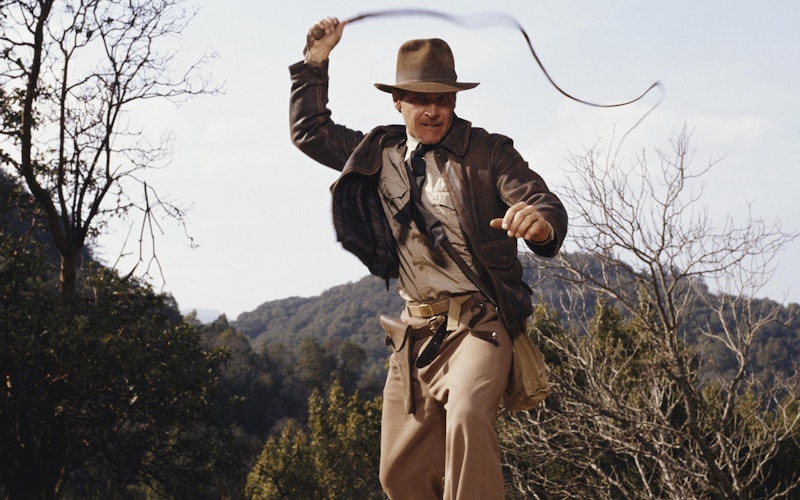

Indy’s whip first appeared in 1981’s Raiders of the Lost Ark. In one of cinema’s most iconic introductions of a main character—courtesy of Steven Spielberg, who directed the first four films in the series—we even see the whip before we see Indy’s face, as it dangles from his belt while he stands, in silhouette, at the edge of a jungle. Traversing through the greenery with two assistants following, Indy stops to consult a map. One of the men—a betrayer—draws a gun behind him and cocks it, the sound prompting Indy to snap the gun out of the would-be assailant’s hands with the strap. After the coward flees, Indiana Jones coils his whip and steps into the sunlight, where we can finally see him in full.

As the series proceeds, you can rank the quality of the movies by how they employ this signature prop. It’s crucial to the climax of that opening sequence, in which Indy is betrayed by the remaining man (Alfred Molina) after obtaining an idol from a booby-trapped temple. (“Give me the whip!” Indy demands from one side of a suddenly opened chasm. “Throw me the idol!” the traitor responds.) The best film in the series by a whip’s length, Raiders follows the lead of that opening set piece by repeatedly featuring the strap as an icon of salvation. Consider the moment Indy flicks a hot poker out of the hands of the Nazi who is holding it against the face of Marion (Karen Allen). Or, later, when he climbs its length in the claustrophobic Well of Souls to the top of a statue, which he then topples through a wall, creating a pathway toward life-giving air.

In contrast, look at 1984’s Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, the second film in the series and a prequel to Raiders. Among the movie’s many miscalculations (its scenes of human sacrifice and child enslavement helped usher in the PG-13 rating), Doom misunderstands the place of the whip within the Indiana Jones mythos. Things are off-kilter from the start, with an elaborate action sequence set in a nightclub that’s dominated by Thompson machine guns. The whip doesn’t even show up until much later in the film, when Indy uses it to hang an assassin from a ceiling fan—a rare, fatal employment. Then there is the scene in which a captured Indy is whipped by his own whip. (Blasphemous!) In the film’s postlude, Indy gently loops it around the waist of his love interest (Kate Capshaw) and tugs her into an embrace. Given that Capshaw’s screechingly irritating Willie is the most poorly written character in the series, this may be the silliest use of the prop yet.

TC Podcast: Indiana Jones' Profession of Faith (Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny)

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, released in 1989, would get things back on track—beyond that escape from the jaws of the lion mentioned earlier. Later in the film, when the adult Indy is attempting to rescue his father (Sean Connery) from a Nazi stronghold, he uses the whip to swing from one roofline to another, then through the window of the room where his father is being held. During the movie’s signature action set piece, much of which takes place on the top of a rumbling tank, Indy saves his father from being crushed under the vehicle’s treads by coiling the strap around his ankles and pulling him to safety. It’s almost as if the whip turns the tank into a plowshare.

I’m a defender of 2008’s Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, which echoes Raiders’ opening scene at its own beginning. Surrounded by Soviet soldiers, Indy uses the whip to snatch a machine gun from an adversary, flip it to his friend Mac (Ray Winstone), then steal a second gun for himself. During the movie’s bombastic climax, Indy tries to save Mac (despite his multiple betrayals by that point) from disappearing into a voracious alien portal. But that proves to be one force for which the whip is no match.

Crystal Skull also has a missed whip opportunity. When Indy and Marion get stuck in quicksand, the movie chooses a lame snake gag over a chance to feature the series’ salvific icon. This just goes to show that my theory isn’t perfect. In fact, the nadir in the franchise is another disavowal of its crucial prop. Facing an intimidating swordsman in Raiders, Indy ignores the whip in his hand and instead pulls out a pistol, shooting his adversary in cold blood. (The behind-the-scenes story about that moment suggests that featuring the gun was a last-minute decision.)

This Raiders misstep is a reminder that Indiana Jones exists, as all of us flawed humans do, in the “already but not yet”—that space between Christ’s ushering in of God’s kingdom on the cross, which Isaiah foretold, and the kingdom’s ultimate fruition in the new creation. At that time, swords will be beaten into plowshares, spears into pruning hooks, and there will be no need for any kind of whip.

Topics: Movies