Culture At Large

Listening to Edvard Munch's Scream

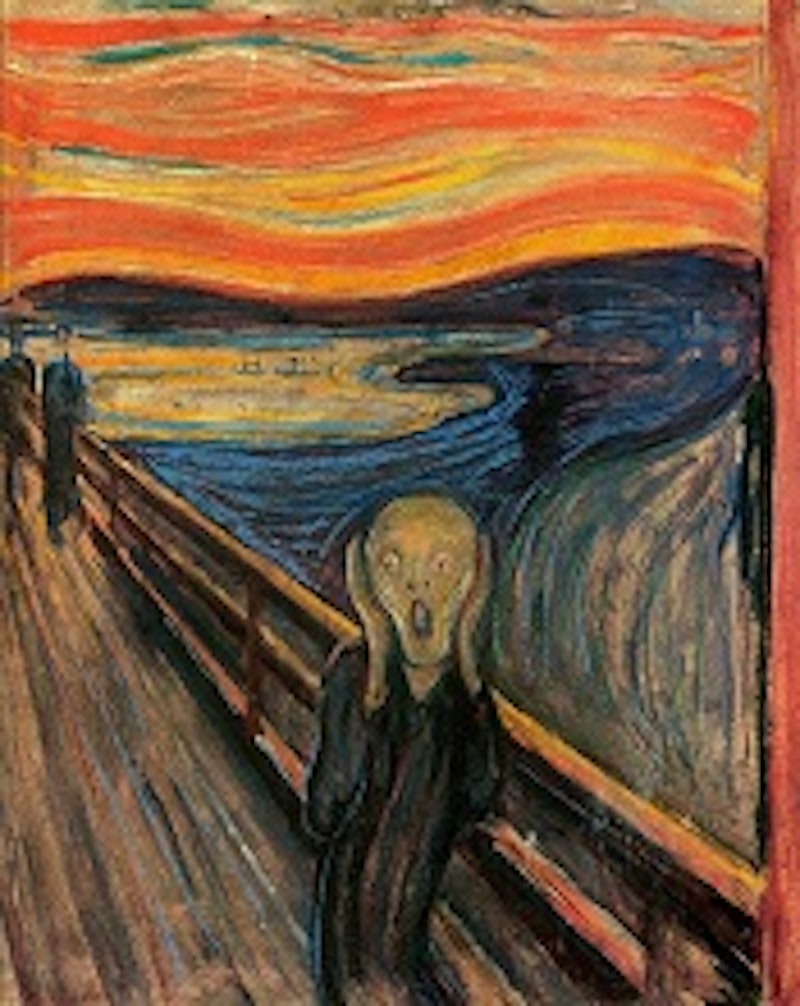

Last week, Edvard Munch's 1895 pastel version of The Scream went under the gavel at Sotheby’s to set a new record as the most expensive piece of art ever sold at auction. One of our culture’s most recognizable and reproduced images, it rivals even the Mona Lisa for the irreverent parodies it has inspired. Yet despite its proliferation as an overused trope, there is something about Munch’s work that remains enduringly fascinating once we begin to peel back the layers of pastiche.

Munch created four versions of his fin de siècle masterpiece, and though they differ slightly in color and composition, all are painted with those broad and undulating bands of garish and exaggerated colors that amplifyandgive visual form to the cry of a skeletal figure in throes of desperation. The figure, while autobiographical, is not a portrait, but fear personified. As it sways, the world around it is distorted. Sky, harbor and sea bend and contort as if they are echoes of the scream. The image is potent visual shorthand for something most of us have experienced: a sense of helplessly corybantic anxiety.

Munch was inspired by a sunset stroll along a path running over an Oslo fjord where he could hear howls emanating from both the asylum where his sister was incarcerated and an abattoir where animals were being slaughtered. In that moment, he recounted, “I stood there trembling with anxiety - and I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature."

Anxiety, defined in medical terms, describes an inner state of inquietude that usually manifests itself through a series of external disorders and phobias. All of us have felt anxious at one time or another, but often that is linked to some kind of empirical threat. Students may feel anxious about final exams or a business owner anxious at the state of the economy. To understand the type of anxiety Munch was trying to describe we need to use another word: angst. Angst is a Norwegian word that entered the lexicon through the writings of the philosopher Soren Kierkegaard to describe a feeling of deep-seated spiritual isolation in which existence seems to have no overriding meaning or order.

For this reason, The Scream has been widely interpreted as representing the universal anxiety of the human condition in a post-Nietzschian world where God has been declared dead, followed by the terrible realization that we have nothing to replace Him with. Munch was born and raised under the stern tutelage of his pietistic father, a poor army doctor whose hellfire and brimstone version of Christianity planted the seeds of his spiritual dread. Later, he would abandon the beliefs that had shaped his childhood. For Munch, The Scream represented his final breaking point from a judgmental God distorted by the lens of wrath.

I wonder if this helps to explain our cultural fascination with the image? As Kierkegaard pointed out, angst attends the life lived without God, and as Munch himself pointed out, the image was designed as a type of icon “for the godless age." Perhaps it remains an icon for us because it captures the religious disillusionment of our age as well.

For Kierkegaard, however, angst was not the end of the story. It was not a disorder, he argued, but God’s way of calling us to commitment. It is only when we get to the place of complete and utter helplessness, so vividly represented in The Scream, that we can take a leap of faith into the waiting arms of God. It is grace, in the end, that remains the sole exception to our psycho-spiritual tragedy.

What Do You Think?

- Does The Scream still affect you or have the countless reproductions caused the painting to lose its power?

- Does understanding Munch’s journey away from God (and his purpose to create a godless icon) make his Scream more or less appealing to you?

- What other art has captured this sort of severe spiritual angst?

Topics: Culture At Large, Science & Technology, Philosophy, Arts & Leisure, Art, Theology & The Church, Theology