Music

Marvin Gaye's radical relevance

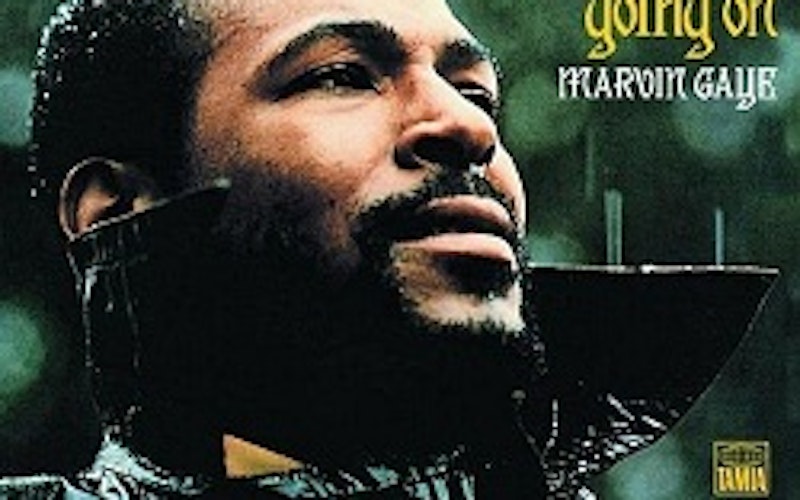

Friends and previous housemates in Michigan might recall my advocacy, during dinner parties and other events, of a certain album. Listening to it twice in its entirety on a recent road trip, I was reminded of the radical relevance of Marvin Gaye’s 1971 creative breakthrough, "What’s Going On."

On a personal level, this album was a gateway for me into the rich streams of soul and R&B music. But on this trip, in particular, I realized that I cannot overstate the profundity of what this album has to say to our current political, cultural and spiritual condition.

The first two tracks on the album, “What’s Going On” and “What’s Happening Brother,” show us how individuals and communities are transformed — the epiphany of compassion, spiritual and social — through the basic observations, questions and conversations of everyday life:

Mother, mother, There’s too many of you crying. Brother, brother, brother, There’s far too many of you dying…. Father, father, We don’t need to escalate.

What would it take for our society to make (or return to) such simple, radical observations?

Talk to me So you can see What’s going on. Ya, what’s going on. Tell me what’s going on, I’ll tell you what’s going on.

In form as well as content, these songs embody compassion and communication - not only do they recommend these acts to listeners, but each song is staged as a conversation or, at least, an internal monologue that wrestles with love and tragedy. As the second track continues to question: “When will people start gettin’ together again? / Are things really gettin’ better, like the newspaper said? / What else is new my friend, besides what I read?”

As I head to graduate school, I’ve been reflecting on hospitality and friendship, which are the themes of a recent conference I attended as well as my upcoming semester-long colloquium. On the plane ride home, I perused a volume of philosophers’ writings on friendship. I loved the book, but was left hovering in abstraction. As Kierkegaard sardonically inquires, “For do you believe that your education or the enthusiasm of any man for gaining an education has taught either of you to love your neighbor?" Enter Marvin with his quiet, devastating supplications.

In contrast to some of the forms of populism that have emerged in recent years, this album’s vision of outrage, of personal responsibility and civic restoration could be life-giving. Even the most candid expressions of outrage are grounded in compassion, awareness and an existential feeling for the tragic: “But who really cares / who’s willing to try / yes, to save a world / yes, save our sweet world / to save a world that is destined to die?” (“Save the Children”). Prophecy supersedes politics here — “live for life,” as a later verse says. It’s astonishing, at times, how far from this ideal we currently are.

Pitchfork’s review of the 40th anniversary edition notes the universality of these messages: “But this album isn’t just a protest time capsule. Far from it. Gaye’s disappointment isn’t just societal, it’s personal as well.” This capacity for double vision - perhaps stemming from double consciousness, as W.E.B. Du Bois called it — is the result of injustice and oppression. Yet it could be the only way our society as a whole can attain Du Bois’ goal of psycho-social reconciliation, or “true consciousness.” It’s soul power, in this sense.

At the Indianapolis Museum of Art, I recently saw Thornton Dial’s expansive catalog of this history. In "Green Pastures: The Birds That Didn’t Learn How to Fly," layers of cloth, wire, enamel and tar-soaked rags manifest the irony, violence and hope that support such power. “White supremacist ideology is based first and foremost on the degradation of black bodies in order to control them,” Cornell West writes.

At the same time, what could our society learn by acknowledging this history of degradation and its ongoing realities? Again Kierkegaard is relevant: “Wherever Christianity is, there is self-renunciation, which is Christianity’s essential form.” Neither personal redemption, nor radical democracy, nor love of neighbor are possible without first divesting one’s self of self-recognition and, instead, recognizing the death that precedes and accompanies our lives.

And in the meantime, we are left with Marvin Gaye’s apocalyptic response, one that is still radically relevant: “Make me wanna holler / throw up both my hands.”

Ryan Weberling is an intermittent student, teacher, writer and day laborer. You can read more of his writing at http://rrrrrrr.org/. This piece original ran in Catapult Magazine.

Topics: Music, Culture At Large, Arts & Leisure, Books, Theology & The Church, Faith, Theology, News & Politics, Social Trends, History, Justice