Music

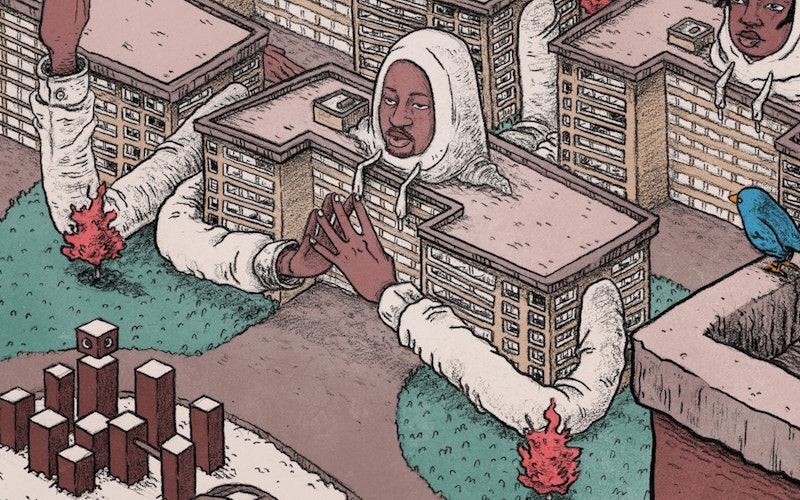

Open Mike Eagle and 'Brick Body' Temples

John Mayer famously sang of bodies as wonderlands. Arcade Fire’s Win Butler cried that his body was a cage. On his new record, hip-hop artist Open Mike Eagle regards bodies as temples being torn down brick by brick.

A visionary concept album about concepts we’d like to avoid, Brick Body Kids Still Daydream tackles gentrification and the disposability of black bodies. The record’s locus is Chicago’s gone-but-not-forgotten Robert Taylor Homes. The once massive housing project met a distinct end, yet could stand in for any shelter that has met a wrecking ball in the name of “progress.”

Eagle connects dots that, to many listeners, might seem to exist in completely different neighborhoods. “I thought about the policy of erecting and destroying housing for black people, and the link I perceive between what happens to those buildings and what happens to black people’s bodies when they are murdered by the police,” he told NPR. “It all hurt a lot and stressed me out. I decided to go harder at it with my writing.”

Eagle pushes hard, and the wound throbs. The long shadow cast by Robert Taylor Homes haunts his lyrics. He admits life in the projects is tough, but mourns their shaping influence. In “Daydreaming in the Projects,” the housing development is a seat of resilience and imagination. On “Brick Body Complex,” he tells how these buildings made him a man: “I’m from a line of ghetto superheroes ... A giant and my body is a building.

No matter how beautiful or basic, home is sacred.

Eagle hammers home the connections between flesh, blood, brick, and mortar in music that recreates all the noisy chaos of a construction site, as when we hear the scrambled signals of a classic soul station piped in from a nearby radio. At times, his vocal delivery has the hard drive of a jackhammer; at others, the smooth flow of concrete filling in the cracks.

Taken as a whole, the record comes off like the soundtrack to a modern John Henry-versus-the-steam-drill story, in which one man works with all his might to beat back the devastating forces of development. Joining sound and substance, Eagle takes his place in a long line of black artists meditating on the devastation the powerful have exacted on black neighborhoods and bodies.

Christians know that, despite homespun wisdom to the contrary, no house really is a home. We are “foreigners and exiles” in this world. The point of our redemption, in fact, is to tear down any walls, man-made or supernatural, that keep us from dwelling in unity with God. We worship Jesus, who let his temple be torn down and rebuilt so we could be at home with him.

That is all good theology, but it can ring hollow for those who have seen the only shelter they’ve known topple.

Eagle’s righteous anger is fully unleashed on the album’s closer, “My Auntie’s Building.” There, he delivers words with their own power to level structures and sacred ideals:

They say America fights fair but they won’t demolish your timeshare

Blew up my auntie’s building

Put out her great grandchildren

That building cost 10 million

Now an empty lot not filled in

It was people there and kids there

And drug dealers and church folk

And they hit that s--t with a wrecking ball

So hard thought the whole earth broke

No matter how beautiful or basic, home is sacred. Physical displacement makes it hard to believe in ever being spiritually settled. When we lose our sense of home, we feel the brokenness that reverberates through the earth like a steady stream of aftershocks.

Eagle’s work on Brick Body Kids Still Daydream finds a strange comfort and cohort in the lyrics of the Eagles. That band’s “The Last Resort” indicts humanity for spoiling the beauty of its surroundings. In a suckerpunch of a last stanza, Don Henley takes us to church:

And you can see them there on Sunday morning

Stand up and sing about what it’s like up there

They call it paradise, I don’t know why

You call some place paradise, kiss it goodbye

As “My Auntie’s Building” closes, collapsing in fits of rubble and white noise, Open Mike Eagle repeats this elegiac phrase: “That’s the sound of them tearing my body down to the ground.”

Christians are right to pine for our promised sacred home and to worship a God who is himself our shelter. But as we do, we must survey the landscape around us. We must see the refugee, whether they’ve been turned out of their home due to civil war or the battle over a neighborhood. We must consider the person who can’t feel at home in a body that is constantly threatened.

Our affirmation that the body is a temple, our full-throated singing that this world will be redeemed, is only good news when we also affirm how far the world has fallen. We really don’t have the right to sing about our hope for the next life until we mourn the ways hope is demolished in the here and now, and roll up our sleeves to rebuild it.

Topics: Music, Culture At Large, Arts & Leisure