Music

Sinners, Saints, and DMX

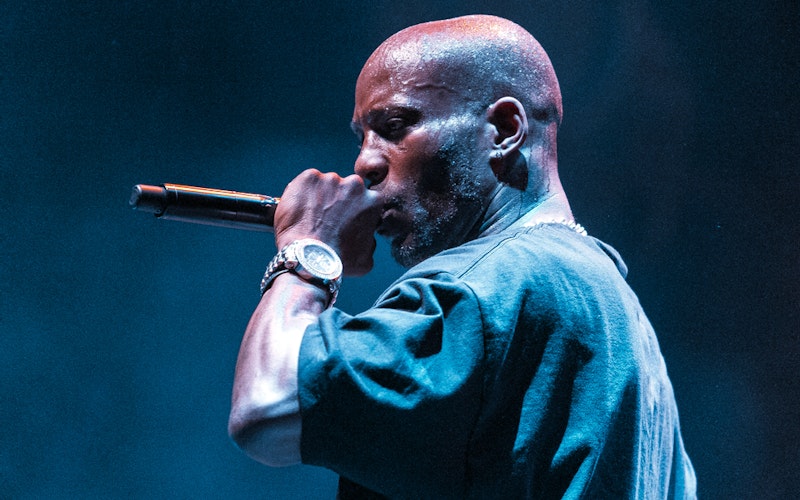

I saw DMX in concert in the spring of 2000. He exploded onto the stage with an infectious energy that he carried throughout his performance. By the end, though, he was in tears, his face in his palms in prayer, his voice penitent, strained and raw. It was not an unexpected moment from an artist who’d already expressed, through his music, an intimate and indefatigable love for God, despite leading a decidedly ungodly life. While he was not a “Christian rapper,” he consciously used his music—and his life—to present a sincere love for God. DMX died last week at the age of 50, a tragic casualty of his demons, yet also a symbol of God’s unwavering grace.

DMX (short for “Dark Man X”) had long struggled with his mental health, including bouts with bipolar disorder and depression. At 14, he was tricked by an older friend into smoking crack, which sparked a lifelong battle with addiction (one that may have caused his fatal heart attack). His sudden death was all the more surprising given that he’d seemed on the mend, making film cameos, looking healthy and sober, performing music again. He’d re-dedicated his life to God, leading virtual Bible studies, claiming he’d been called by God to be a preacher. So how do we reconcile that call with his deliberate image as a violent criminal, spitting tales of larceny, assault, and murder? How can we fully separate the sinner from the saint?

The answer is that we can’t. DMX certainly couldn’t, and his music reflected this contentious marriage of conflicting personas. We see this illustrated through a pair of tracks from his debut album, It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot. On “Damien,” X alters his voice to rap as two separate characters: himself and the impish Damien, a supposed “guardian angel” who promises the hungry rapper wealth in exchange for his loyalty. “I'm about to have you drivin', probably a Benz,'' Damien says, “But we gotta stay friends: blood out, blood in.” He swears to keep X’s darkest secrets, while encouraging him to indulge in destructive behavior: drugs, excessive drinking, reckless fornication. In gratitude for Damien’s “friendship,” the lonely X pledges his right hand (because “Yo, that’s my man!”). But he ends up with more than he bargained for when Damien starts asking for deadly favors in return.

We hear a different story on the track “The Convo,” where we find X still “confused and full of questions / Am I born to lose or is this just a lesson?” He again plays the dual role of himself and the voice in his head, which this time reveals itself to belong to God. Unlike Damien, God dissuades X from robbing to feed himself: “Put down the guns / And write a new rhyme / You'll get it all in due time . . . ” Like Damien, God watches over X “at those times you least expect it;” unlike Damien, he proves to be a source of protection and comfort in the rapper’s darker moments. Speaking to God, X says: “A few of them times I thought you would erase me / When all you did was embrace me, prepared me for the worst / Offered me eternal life and scared me with the hearse / And the curse turned to grace when the hurt turned to faith / No more runnin' or slidin' in the dirt, 'cause I'm safe.”

TC Podcast: Backsliding (DMX, The Falcon and the Winter Soldier)

This apparent contradiction came to exemplify the life of DMX. The rap icon born Earl Simmons found record-breaking success in his long career, releasing two platinum albums in the same year and going on to sell over 70 million albums worldwide. It was a far cry from his childhood in Yonkers, where he suffered extreme poverty and abuse. His lyrics recalled an early life mired in crime—from purse-snatching to car-jacking to killing. Literally barking his rhymes, he often expressed more of an affinity for the stray dogs he befriended while living on the streets—hungry, abandoned, and dangerous when pushed. Yet, at the same time, he included a prayer to God on each album, seeking forgiveness, or extolling gratitude, even praying for the same enemies whom, only minutes before, he’d threatened to punish himself. The emotional scene at the show I attended revealed a man conscious of these contradictions, even trapped by them, fueling a pain that proved, in the end, inescapable. That he laid bare his pain for his audience, up until the end, is what made him the preacher that he aspired to be—an imperfect preacher for an imperfect people of faith.

Indeed, the beauty of God’s grace is that it’s bestowed on saints and sinners alike. And if we believe in the transformative power of faith, then we must also acknowledge the need, in all of us, to transform. We can only truly appreciate the light once we’ve spent a little time in the dark. What made DMX a symbol of God’s grace was not his impassioned invocation of God, the biblical allusions he made, or even his cameo at Kanye West’s Easter Service at Coachella 2019. No, X's real gift as a preacher and his value to people of faith was his insistence that God’s grace is not reserved for the godly alone—that it’s bigger than the box to which it’s so often confined. And so let’s honor the late Earl Simmons for opening that box wider, with an excerpt from one of his own “Prayers” as a benediction:

And I fear that what I’m saying won't be heard until I'm gone.

But it's all good, 'cause I really didn't expect to live long.

So if it takes for me to suffer, for my brother to see the light.

Give me pain till I die, but please lord treat him right.

Topics: Music