TV

The Awkward Promise of The Office

On paper, there's no reason The Office should be one of the most beloved sitcoms of all time. It's an American remake of a British show, about a cubical farm in small-town Pennsylvania. And it's awkward. Really awkward. Nevertheless, The Office ran for 201 episodes and won almost 30 awards, including Emmys and Golden Globes. Despite having been off the air since 2013, it remains popular on streaming services, where it has found a new generation of fans.

Why does such an awkward show have so much appeal? Perhaps because The Office employs awkwardness as an invitation for viewers to choose compassion rather than contempt, even for its most embarrassing characters.

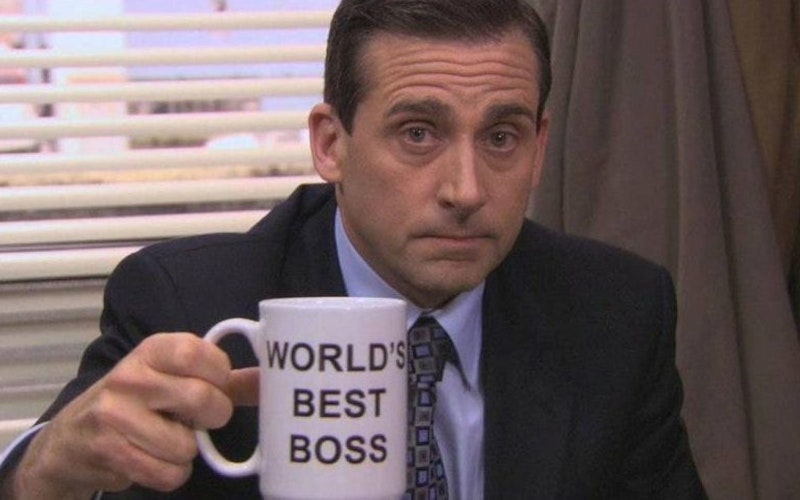

In the pilot episode, we meet Michael Scott (Steve Carell), a regional manager for Dunder Mifflin, a failing paper company. A film crew documents the work life of Dunder Mifflin employees in the Scranton branch, where Michael presides. In his office, he displays for the camera a coffee mug that reads "World's Best Boss." His eyes gleam as he shares the pride he feels when he considers the title this mug bestows upon him. Then he says, "I found it at Spencer's." Awkward.

Melissa Dahl, author of Cringeworthy: A Theory of Awkwardness, describes awkwardness as "an unpleasant kind of self-recognition where you suddenly see yourself through someone else’s eyes. It’s a forced moment of self-awareness, and it usually makes you cognizant of the disappointing fact that you aren’t measuring up to your own self-concept."

Michael sees himself as the "World's Best Boss." He even bought himself a mug to celebrate that fact. Yet we don't have to watch the whole pilot to see that Michael is (self-)delusional. We know those mugs are designed as gifts. We know that anyone who would buy themselves such an item is likely pretty far from the World's Best anything. So we see the gap between Michael's self-concept and the reality of how Michael is experienced by his employees: as selfish, self-absorbed, and tone-deaf.

The show's documentary format is essential to making the awkwardness work because the characters are always conscious that they're being watched. Later in the pilot, when Dwight (Rainn Wilson) insists Michael punish Jim (John Krasinski) for putting Dwight's stapler in Jell-O, Michael is unable to suppress his giggles and tells Dwight he has to eat the gelatin "because there are starving kids in the world." Then, as he glances at the camera and remembers he's being recorded, he clears his throat and intones in a deeper, performative voice, "Which I take very seriously." In the space of seconds, we watch Michael shift from his authentic self—a man who makes jokes about world hunger—to his performative self: a man virtue signaling to appear compassionate and admirable.

While Michael seems unaware of the gap between his two selves, we viewers cannot escape it. Faced with the stark difference between who Michael imagines himself to be and how Michael is experienced in the world, we cringe. It's awkward.

We cringe when others make things awkward because of what psychologists call “empathy.” Empathy is the ability to put ourselves in someone else's shoes. Generally, we think of empathy as a good thing. But in her book, Dahl suggests that empathy is not automatically good. One group of people who score high in empathy are, surprisingly, Internet trolls. In order to “troll” effectively—to comment in such a way as to insult or hurt a person—you have to understand them.

How do we make sense of this? Some psychologists split the concept of empathy into two kinds: cognitive empathy and compassionate empathy. With cognitive empathy, we can understand what the other person is thinking and feeling, but we keep them at arm's length. This lets us manipulate or laugh at them. Compassionate empathy, on the other hand, is when we let ourselves identify with the other person; to really feel what they're feeling and to stand in solidarity with them.

We see the gap between Michael's self-concept and the reality of how Michael is experienced by his employees.

Empathy and awkwardness are also at play in one of the stories involving King David in the Bible: Nathan's confrontation with David. David was king of Israel, and by the time of the events recounted in 2 Samuel 11, it's safe to say no one was buying him a World's Best King mug. After his predatory sexual pursuit of Bathsheba, the wife of one of his soldiers, she became pregnant. In his quest to cover up his sin, David demonstrated significant cognitive empathy. He called the soldier home from the front lines, wined and dined him, and sent him to his home to sleep with his wife. David, a former mercenary himself, understood the peaks and valleys of a soldier's marriage. But when the man refused—out of loyalty to his brothers in arms still on the battlefield—David dropped all pretense and arranged to have him killed.

David was king, so no one could hold him accountable—except for God's prophet, Nathan. God instructed Nathan to confront David, which he did by way of a story. He described a wealthy man who stole a poor man's prize lamb rather than use one from his own flock. The story activated David's compassionate empathy; he became furious at the injustice done to the poor man and demanded retribution. It was only then that Nathan sprang his awkward trap, revealing, "You are the man!"

At that moment, David's self-image was shattered. His delusion of being a godly, just king was laid bare before the reality that he was an abuser.

This is the power of the awkward moment: we have the choice, when faced with the vulnerability of another, to respond with either compassion or contempt. The genius of The Office is that, over its 201 episodes, it shows us the vulnerability of even clueless buffoons like Michael Scott. It's easy to (rightly) condemn Michael’s antics. But from the beginning, Michael was meant to be sympathetic, too. Writing about this intentional decision on the part of the show’s creators (which is a major distinction from the original British version), Corey Chichizola observes, “As The Office continued to unravel Scott’s personality, we saw how terribly he wanted friendship, love, and a family. He went from being the frustrating character on the show to the one who could make us cry at the drop of a hat.”

It's no surprise that this kindness toward frustrating characters became a centerpiece of the storytelling of Michael Schur, a writer on The Office who has gone on to create other hit sitcoms like Parks and Recreation, Brooklyn Nine-Nine, and The Good Place—all shows renowned for their optimistic, bright core despite featuring often incredibly cringeworthy characters.

In our increasingly polarized world, contempt is becoming a reflex. We see an instance of awkwardness and we pounce. But kindness is a much-needed fruit of the Spirit, one that people of faith are called to cultivate. Perhaps watching The Office can be a spiritual practice, then; one that reminds us to compassionately choose kindness, whether in our cubicles or in our churches.

This article was originally published as part of our free Theology of The Office ebook.

_______________

At Think Christian, we encourage careful cultural discernment. We recognize and respect that many Christians choose not to engage with pop culture that contains particular content, such as abuse, sex, violence, alcohol or drug use, or that employs the use of coarse language. To that end, we suggest visiting Common Sense Media for detailed information regarding the content of the particular pieces of pop culture discussed in this article.

Topics: TV