Culture At Large

The boy who cried heaven – and the belief industry that encouraged him

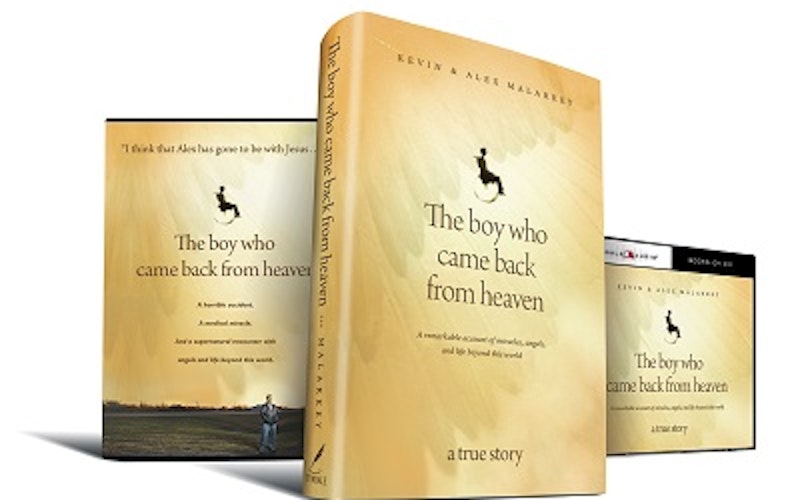

Last week, Tyndale House Publishers stopped production of The Boy Who Came Back from Heaven after Alex Malarkey, the boy in question, announced that he had made up the tale. Cheeky jokes about the family’s surname aside, this is a serious matter that shouldn't go gently away, but rather stand as a reminder of what it means to speak for and about God, the Christian life and the kingdom at hand.

Years ago, when author James Frey was taken to task for his composites of characters and situations in his jarring book A Million Little Pieces, the publishing world - both Christian and mainstream - erupted in a debate about truth: what it means to tell it, and how it should be told. Sadly, this was not a lesson to which those behind The Boy Who Came Back from Heaven paid attention. Eager to offer a vision of the afterlife that was well suited to the commercial evangelical machine, Tyndale allowed a 6-year-old and his father (mostly his father, Kevin Malarkey) to speak about ecclesiology with flippant idealism and day-dreamy cliché, dangerously undergirded with a misinterpretation of Christ’s saying about praise from “the mouths of babes.”

I say this in no way to heap guilt onto a 6-year-old (though he is now 16). After all, he couldn’t have told his story without the help of several adults eager to provide evidence of heaven. Yet we don’t need a crappy book to prove what the Bible promises, as proof of it negates the necessity of/for it, and destroys the imagination so integral to living a full Christian life.

We don’t need a crappy book to prove what the Bible promises.

And that is the first problem: that this book set out to prove something that cannot be proven, because believing it is an act of faith. While the market demands such proofs, publishers and authors have higher responsibilities to what that truth is and to bearing it with the imagination it deserves. Whether one believes in an imminent heaven here on earth or an afterlife paradise or both, it’s clear to any person of genuine faith that such a thing is not worth trying to prove, as it ruins the beauty of belief.

Unfortunately, we will continue to sacrifice the truth of the imagination on the altar of the literal. Instead, we should be embracing imagination for what it is: a wonderful, God-given tool for divine empathy, compassion and enlightened thinking - not to mention just plain fun. I’m a Christian who cares about literature and poetry (shame on me), which is its own liability in both the Christian publishing world and the mainstream literary world, though the perils look different in each. Had The Boy Who Came Back from Heaven been published as a piece of fiction it would not have been a bestseller, and perhaps wouldn’t have been published at all.

Alex Malarkey, who shouldn’t be taking the fall here, told this story years ago doing what children often do: spin fairytales for the sake of engaging, understanding and exploring the world, especially in light of tragedy. That doesn’t mean we need to hold them up as evidence for belief by making them into pieces of nonfiction - only adults engage in such frivolous silliness and irresponsibility. The boy's co-author father and the folks that shepherd such books into print have to be more careful with the imaginations of the people who trust them - and own up to their mistakes when they make them. Which reminds me of another teaching of Jesus, where he talks about millstones, necks and those who claim to teach.

Topics: Culture At Large, Arts & Leisure, Books, Theology & The Church, Faith, Evangelism