Culture At Large

The good that comes from reading about Horrible Things

One of the first Holocaust novels I read was Lois Lowry’s Number the Stars, which tells the story of 10-year-old Annemarie Johansen and her family as they rescue Jews from Nazi forces in Copenhagen, Denmark. I was too young to grasp World War II’s immensity - the international impact, the strategic sweep of Hitler’s deception. But I was thrilled by the narrative in my hands. On the cover, Annemarie - with her short, white-blonde hair and light eyes - looked a bit like me.

I now know that over six million Jews perished in the Holocaust, a statistic that will forever haunt the world’s conscience. Only recently, though, did I read an estimated WWII death toll considering all of its elements - from the camps to the bombs to the battlefields.

This figure is 66 million dead.

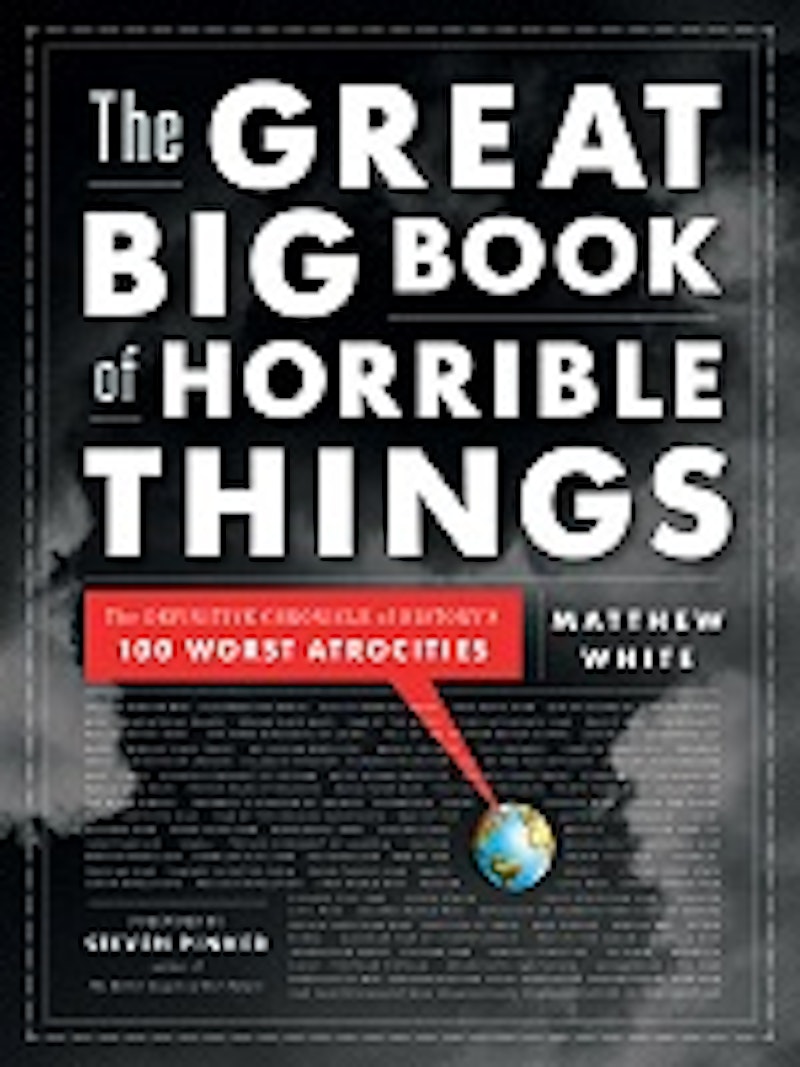

I read it in a book much different than the historical novels of my youth - a 560-page text called The Great Big Book of Horrible Things: The Definitive Chronicle of History’s 100 Worst Atrocities.

Rather than offer a fictionalized or first-person view of our world’s most violent chapters, this giant, chronological resource ranks them by body count. The history of violence begins with the Persian War (480-479 B.C.) and ends with the Second Congo War (1998-2002). In every event at least 300,000 were killed. WWII tops the list.

The author, Matthew White, isn’t a multi-degree scholar; he’s a librarian, blogger and self-termed “atrocitologist.” White bends the encyclopedia-entry formula by adding quirky categories, first-person asides and playful terms. Mongolian conqueror Genghis Khan, for example, is called “the absolutely baddest badass in human history.” This is no tame school textbook.

I’m still working my way through Horrible Things. Already, though, I sense possible criticisms it may receive - and not just for the disputability of its data, which White frequently acknowledges. I suspect some may be irked, even offended, by the very concept of ranking atrocity. After all, as White rhetorically asks in his introduction, “Aside from morbid fascination, is there any reason to know the 100 highest body counts of history?”

If I hadn’t actually read White’s book, I may have been among those to dismiss his approach as unreasonable and/or disrespectful. But by three or four chapters in, I recognized its surprising … nobility.

If I hadn’t actually read White’s book, I may have been among those to dismiss his approach as unreasonable and/or disrespectful. But by three or four chapters in, I recognized its surprising … nobility. I believed that White is, as he says, writing in part to emphasize “the human impact of historic events.”

“Yes, these things happened a long time ago, and all of those people would be dead now anyway,” writes White, “but there comes a point where we have to realize that a clash of cultures did more than blend cuisines, vocabularies and architectural styles. It also caused a lot of very personal suffering.”

I deeply relate to White’s desire to be the voice of ordinary people suffering in extraordinarily horrific events - not in a prescribed format, but in his own unique way. Horrible Things has challenged me to see both the stories and the statistics of human suffering as crucial to understanding the bloody, broken reality of our world. As with Lowry’s Number the Stars, I admire White’s book as an attempt to account for and show honor to the lost. This is how I am reading each page - each staggering curve of tragedy in this original, thorough and peculiarly readable book.

And when the sheer enormity of lives lost overwhelms, I can hold on to Psalm 147, to which the title of Number the Stars pays tribute. I can pray and lament to a God who counts and names all creation, and who equips His children with ardent senses of wit and of justice.

May He lead us through even these painful legacies with immense, intimate hope.

(Montage of paintings depicting the 100 Years' War courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

Topics: Culture At Large, Arts & Leisure, Books, News & Politics, History