Culture At Large

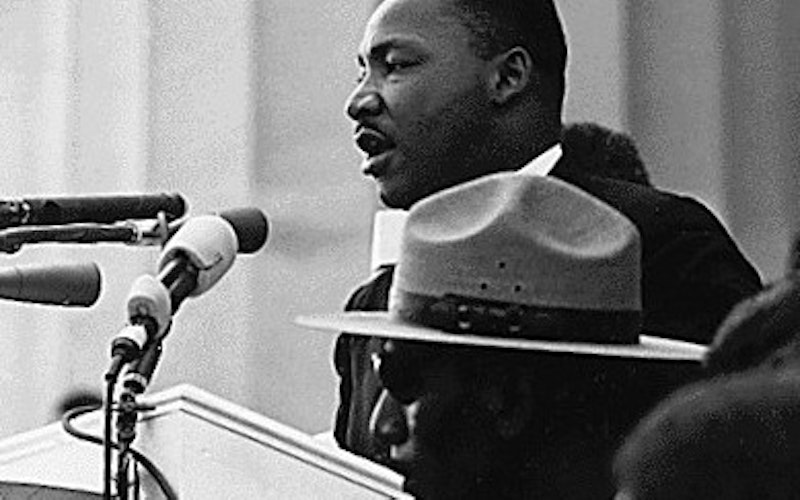

What does the Martin Luther King monument mean?

At age 93, the Rev. Gardner Taylor never thought he'd live to see the day when his friend Martin Luther King Jr. would be honored with a national memorial.

"I think it is singularly appropriate and long overdue," said Taylor, who helped found the Progressive National Baptist Convention 50 years ago to support the civil rights work of the friend he called "Mike."

"Mike King was minister and leader not only of black people," he said, "but he was leading the nation to what it ought to be."

Ahead of the memorial's official dedication, the men and women who worked and marched alongside King said it's important to remember that before he was in the vanguard of the civil rights movement, he was a preacher of the gospel. In fact, "it's really impossible to separate the civil leader from the religious leader," said Taylor, known nationally as the dean of African-American preachers. "He embodied both, and his life was a testimony to the unity of the two."

Designers intended for the memorial to demonstrate what they called King's "spiritual presence," with his 30-foot physical image sculpted in the "Stone of Hope" and a wall of inscriptions that include quotes from his sermons and speeches.

In his "I Have a Dream" speech, uttered 48 years ago to the day of the memorial dedication, King said: "With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope."

The placement of the monument, along the Tidal Basin a stone's throw from monuments to Thomas Jefferson and Franklin D. Roosevelt, is particularly meaningful to the Rev. Otis Moss Jr., who was married 45 years ago by King.

"To have a nonviolent leader, spokesperson and martyr memorialized in the sight lines of Presidents Jefferson, Washington and Lincoln - two of whom were slaveholders and one having a mistress who was black - and to have this moral message is, I think, unprecedented," said Moss, a retired Cleveland pastor. "This is more than stone. It is a statement, a moral statement."

Moss, who was part of the student sit-in movement in Atlanta in the 1960s, said King's words, etched in the stone surrounding his likeness, will help bring life to a figure who achieved iconic status.

"Here was a great moral leader," Moss said, "a philosophical theologian whose teachings and preaching were anchored in the biblical message of love, justice and reconciliation."

It's not enough, however, to simply recall King's work and words. Those who soldiered alongside him say a new generation must pick up where he left off.

"It's a very fitting tribute that will serve, I think, a noble purpose in reminding people of his contribution and how far the country has come and hopefully will encourage people to join in the struggle," said the Rev. Joseph Lowery, a retired Atlanta minister who co-founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference with King and others.

Previewing the memorial with other black Catholics recently, Sister Antona Ebo sat beneath the King sculpture and recalled joining five white sisters in a march in Selma, Ala., a few days after the 1965 Bloody Sunday attacks.

"I was hesitant about going because it was a matter of going and asking oneself, 'Do you want to be a martyr for somebody else's voting rights?'" she recalled.

Nearly a half century later, she said the martyred King is finally appropriately honored in the pantheon of national heroes. "It's his right to be honored in that way," she said, "but he probably would be the most reluctant to say so because of his humility."

The Rev. Charles Adams, a Detroit preacher and Harvard Divinity School professor who worked as an intern for King when he taught at Morehouse College in the early 1960s, agreed.

"His wife called me shortly after he died and said, "You know, my husband isn't about monuments; he's about the movement,'" Adams recalled. "And that's true. I don't think he wants to be fixed in stone, but he wants to be reincarnated into young people who are willing to fight and live and love and die for freedom and for justice."

This article published via Religion News Service. Adelle M. Banks joined the Religion News Service staff in 1995 after working for more than 10 years at daily newspapers in the upstate New York communities of Binghamton and Syracuse, as well as at The Providence Journal and the Orlando Sentinel.

(Photo of Martin Luther King Jr. courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Artist's rendition of Martin Luther King Jr. National Memorial courtesy of Religion News Service.)

Topics: Culture At Large, Theology & The Church, Faith, The Church, News & Politics, History, Justice, North America