Music

Bonhoeffer, Blue Ruin and relinquishing revenge

One of the more eloquent ruminations on revenge that I’ve seen in a while is Blue Ruin, a small, independent movie now playing in select theaters and available to stream online. It’s a rough, riveting thriller that’s two parts Coen brothers and one part Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

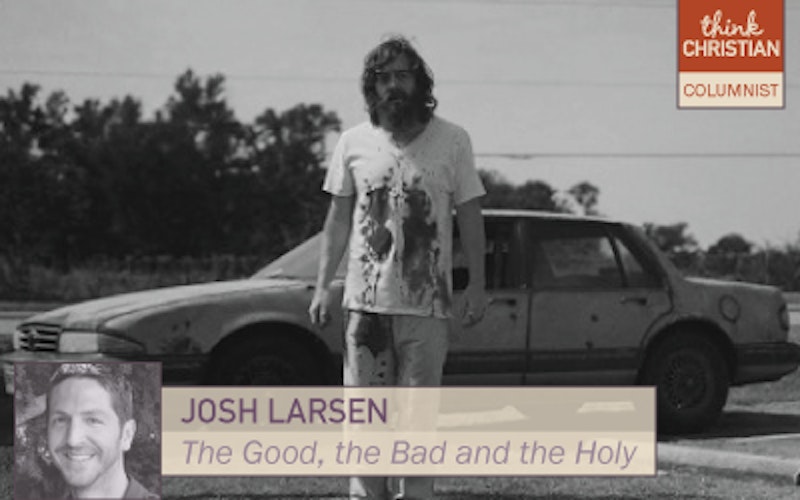

Written and directed by Jeremy Saulnier, Blue Ruin begins by immersing us in the daily struggles of a scrawny, bearded vagabond named Dwight (Macon Blair). Living out of his car, scrounging meals from the trash, Dwight seems content to live life as a nomadic hermit. But then he learns that the man convicted of his parents’ murder is being released from jail. And though there is no reason to think he can pull off such an undertaking – he fails on two occasions to even obtain a gun – Dwight resolutely sets out to avenge his parents by killing this man.

Largely because of Dwight’s ineptitude, Blue Ruin proceeds with a haphazard unpredictability. And yet it’s no comedy. Although Joel and Ethan Coen’s darkly comic Blood Simple is a clear influence, Blue Ruin mostly echoes the doomed, mournful air of their Oscar-winning No Country for Old Men – with Dwight as the accidental Anton Chigurh figure, a bumbling angel of death.

It isn’t until Dwight inexplicably gains the upper hand that the full import of his actions begins to dawn on him.

And here’s where Bonhoeffer comes in. The German theologian, who left the safety of America to oppose the Nazis and was executed by the regime in 1945, devoted an entire chapter of his book, The Cost of Discipleship, to the senselessness of revenge. “The only way to overcome evil is to let it run itself to a standstill because it does not find the resistance it is looking for,” he wrote. “Resistance merely creates further evil and adds fuel to the flames.”

In Blue Ruin, Dwight’s “resistance” ignites a bonfire. And yet the movie is no easy moral lesson, in which Dwight suffers for his choice to repay evil for evil. Indeed, it isn’t until Dwight inexplicably gains the upper hand that the full import of his actions begins to dawn on him. If there’s a definitive scene from the movie, it’s the one in which Dwight holes up in a would-be victim’s house, preparing an ambush, and passes the time by flipping through the family’s photo album.

This brief glimpse of humanity ends suddenly, though, when the people Dwight has been waiting for come home. “Further evil” ensues. In the end, the only one who has any hope in Blue Ruin is the one who walks away. (I won’t tell you who that is.) Bonhoeffer would describe such a decision this way:

When evil meets no opposition and encounters no obstacle but only patient endurance, its sting is drawn, and at last it meets an opponent which is more than its match. Of course this can only happen when the last ounce of resistance is abandoned, and the renunciation of revenge is complete. Then evil cannot find its mark, it can breed no further evil, and is left barren.

One of Blue Ruin’s many virtues is its striking imagery. (Saulnier, the director, has mostly worked as a cinematographer before this.) Early in the film, after Dwight has put his plan into motion, there is a shot of a bloody knife stuck into the tire of a car, rotating endlessly as Dwight speeds away. It captures the vicious cycle of revenge he has thrown himself into and foreshadows the circle of suffering that is to come. Here and there (that photo album, for instance), the movie offers Dwight reasons to opt for Bonhoeffer’s “patient endurance." He chooses ruin instead.

Topics: Movies, Culture At Large, Arts & Leisure