Movies

Christopher Nolan’s Works-Based Cinema

Hands down one of the best directors of our time is Christopher Nolan. From big box-office successes to hidden gems, Nolan movies always deliver. I’ve found three staples throughout his filmography: the distortion/manipulation of time; visual spectacles; and intricate explorations of identity. You can count on Nolan to employ these tactics in an entertaining manner whenever he’s in the director’s chair. As we prepare for Nolan’s 11th film, Tenet, let’s unpack how Nolan’s movies—featuring some of my favorite characters in cinema—compare with a biblical understanding of identity.

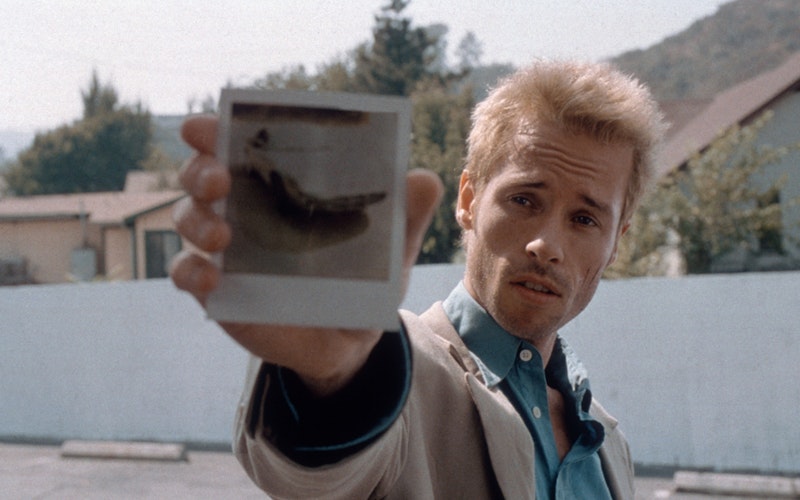

Memento, Nolan’s inventive, critically acclaimed 2000 film, follows Leonard Shelby (Guy Pearce), a man who is on a quest to find his wife’s killer, despite the fact that he has anterograde amnesia and can no longer create new memories. Along the way, he meets various characters who try to help, hurt, and use him. It’s hard for him to distinguish the motives of others, but he develops a system of keeping track of crucial information by tattooing details on his body and writing on Polaroid pictures that he takes.

Nolan creatively opens Memento with the plot’s final scene and works backwards through the storyline as the viewer slowly gathers a deeper understanding of Leonard’s identity: he hates to be called Lenny; he’s not a violent person but he’s determined to kill his wife’s murderer; he can remember his earlier life with his wife, but nothing that happened beyond the point when his amnesia set in, after her death. The film’s nonlinear structure disorients the viewer, mimicking Leonard’s confusion about his own perceived identity and purpose.

So, what constitutes Leonard’s identity in his fragmented reality? Well, Leonard is consumed by one singular focus that ironically he can’t forget: according to his own “clues,” John G killed his wife, and he must avenge her death. He finds his identity in the actions that he takes toward this mission. Near the end (spoilers ahead), it is revealed that Leonard has already killed one John G, and many other surrogate John Gs since then. Teddy (Joe Pantoliano), an accomplice who has been enabling this cycle, explains to him that he is living in forced ignorance; he doesn’t want to remember the details of his wife's death (which I won't spoil). Teddy even exclaims, “I gave you a reason to live. You don’t want the truth.” At this point, Leonard devises a new scheme to make Teddy out to be his newest John G, in order to perpetuate his invented purpose. Without a puzzle to solve, he would not be “himself.”

For Leonard, the pursuit of justice—rather than justice—has become his purpose. It defines him. He has set a path and is determined to walk it over and over again. In Proverbs 3, we are told to trust in the Lord and he will make our paths straight. Leonard, however, only trusts in his mission of vengeance. He has found a way to be lord over space, time, and his own mind in order to pursue a fruitless, circular course of action that will never fully satisfy him.

In Insomnia, a psychological cop thriller from 2002, Nolan expertly uses visuals to expose the heart of his characters. Will Dormer (Al Pacino) is established early on as a morally upright detective from Los Angeles who stakes his identity on his reputation. However, when he is called to Alaska to assist with a murder investigation, his morality becomes fluid. This culminates when Dormer accidentally (or maybe not so accidentally) shoots his partner in a thick fog while trying to chase a suspect. Things become more complicated when we learn that Dormer and his partner (Martin Donovan) had been under investigation themselves by L.A.’s internal affairs division.

Nolan uses the fog as a symbol for Dormer’s increasingly murky sense of morality; what ensues after the shooting is a set of events that pushes him further down a slippery slope of unscrupulous behavior. As a result, Dormer struggles to sleep as he begins to act like a bad cop. One of the Alaskan officers (Hilary Swank) observes: “A good cop can’t sleep because a piece of the puzzle is missing. A bad cop can’t sleep because his conscience won’t let him.” To make Dormer’s situation worse, the sun never goes down during Alaskan summers. Nolan uses Alaska’s piercing glare of perpetual sunlight to expose Dormer’s guilty conscience.

In Luke 12, Jesus warns his disciples to be on guard against the hypocrisy of the Pharisees: “What you have said in the dark will be heard in the daylight. . .” The alignment between Dormer and the Pharisees is almost uncanny. When we are committed to an identity that is built on our reputation more than God, we are doomed to live lives of disappointment. No one can live a life of perfection other than God himself. Any identity built upon perfection is faulty. We aren’t meant to hide our faults in order to solely be perceived by our good works. This only presents a false self and diminishes our own light and witness; it actually destroys our reputation.

Finally, let’s look at the best trilogy of movies ever: Nolan’s Dark Knight series. (I will forever stand by this until God tells me different.) In 2005’s Batman Begins, a young Bruce Wayne watches his parents get gunned down. As an adult (Christian Bale), after failing to get revenge for his parent’s death, he discards all of his possessions in order to find a better way to bring justice to Gotham. This is extremely admirable, but Bruce completely forsakes his name, birthright, and familial connection for this sacrifice. In his travels he meets the radical leader Ra’s Al Ghul (Ken Watanabe), who trains Bruce in combat and tells him that Gotham must be destroyed in order to be saved. Bruce rejects this offer and returns to Gotham a new man, determined to establish justice in his city through action! He dons the attire of Batman in order to become a symbol that transforms Gotham.

However, this creates major tension with Alfred (Michael Caine), his trusty butler, bodyguard, and confidant. Alfred sees that Bruce is overly committed to being Batman and not concerned enough with being Bruce Wayne. Throughout the trilogy—which also includes The Dark Knight and The Dark Knight Rises—Bruce is challenged by Alfred to find an alternative form of crime fighting, one that values the life of Bruce. Nolan uses the duality of Bruce and Batman to represent how one’s internal resolve can motivate external behaviors, even to the detriment of the person. In order to become Batman, Bruce Wayne must sacrifice his personal identity. Here we find the major tension of the trilogy: Bruce is sacrificed for the works of Batman.

Bruce is determined to establish justice in Gotham through action.

Again, we are presented with the idea of identity being determined solely by what one can do at the expense of every other part of the self. This leads one down a destructive path. When Batman is no longer needed in Gotham (as is the case at the start of The Dark Knight Rises), Bruce goes into a deep depression and doesn’t leave his home for eight years. His desire to be sacrificial is honorable, but behind his larger-than-life persona is merely a man. The Dark Knight trilogy reminds us that we aren’t meant to be solely dedicated to a cause, but to God. God will reveal the causes to fight for and bring about his justice, using us in his own way. As is said in the Romero Prayer, written in memory of Catholic bishop Oscar Romero, “We are workers, not master builders; ministers, not messiahs.” It’s not Bruce’s heart for justice that is the actual issue, but his misplaced identity in the fight.

Over his filmography, Nolan’s characters deeply connect their identity with what they do: Leonard’s unending quest for vengeance; Dormer’s defense of his reputation; Bruce Wayne’s obsession with enacting justice. As Christians, we know that our identity is not only determined by what we do, but where our hearts are anchored. When God chose David to be anointed, he told Samuel that he is concerned with the heart! David can rest assured that his true identity is secured in his heart for God—an internal alignment with God. By rooting ourselves in God we learn that he is not only concerned with the actions we take, but also the state of our hearts.

In Isaiah 1, God rebukes his people for offering empty acts of worship and sacrifice that don’t truly reflect the state of their hearts. Nolan’s films reveal this same sentiment. Leonard will never be content, no matter how many John Gs he kills. Dormer will never be able to scrub his reputation so that it’s spotless. And Batman’s justice will fail if he tries to play the part of a sacrificial messiah. We have a Messiah who has defeated death, wiped us clean, and sacrificed himself for us. When we give our hearts to God in gratitude, we will find our true identity and discover the unique path he has designed for us.

Topics: Movies