Music

Drive-By Truckers’ “Thoughts and Prayers”

Word of yet another mass shooting spreads through social media, and the song that follows remains the same. Deep notes of grief meet agitated rhythms of blame and flat melodies we’ve heard a hundred times before. The resulting dissonance never quite resolves.

Patterson Hood wants to sing a new song. Drive-By Truckers’ co-leader offers more than just his “Thoughts and Prayers” on a cut from the Georgia band’s new offering, The Unraveling. The track represents the latest in a recent series of overt political declarations from a group that has never shied from hard conversations.

For nearly 25 years, the Truckers have wed the neon charge and liquid courage of a bar band to a Southern Gothic strain that delights in telling literary tales of morally conflicted characters. Their songs run headlong through the South’s prickly cultural briars, threading thoughts on racism, patriotism, old-time religion, and sexual politics through their catalog.

Aging defiantly, the band keeps cranking up the gain on its guitars and its dissent. “What it Means,” situated within the searing 2016 album American Band, attempts to make sense of the deaths of Michael Brown and Trayvon Martin and illuminates differences between Black and White America. Released a year later, “The Perilous Night” is a chugging warning about authoritarianism; this is what Paul Revere’s ride might have sounded like if The Rolling Stones called “shotgun.”

On “Thoughts and Prayers,” Hood’s twang drips with disgust and disappointment over America’s lack of progress on gun violence. He sings free of affectation against a steadfast acoustic strum, lively drums, searching electric guitar, and Jay Gonzalez’s poised piano. Initially, the lyrics don’t lay particular political blame for our cycles of terror and inaction; Hood’s hellfire and brimstone scorches any American who responds to tragedy from a place of remove.

With each verse, Hood and Co. tighten the screws. No institution is safe when he fixes his gaze. With the line “Glory hallelujah / You are in our thoughts and prayers,” he mocks the Church for what he feels is a hollow response. In a curious line, Hood invokes flat-earthers undone by ignorance; a seeming digression underlines his fear America will collapse under the weight of an unwillingness to engage plain but difficult truths.

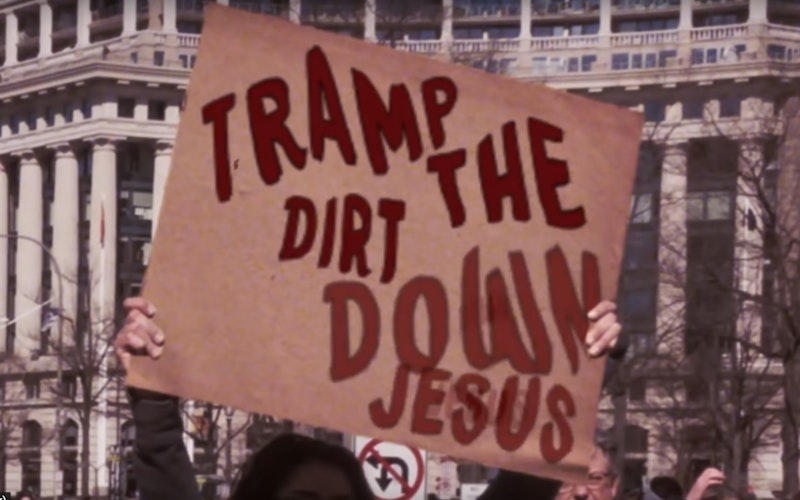

In the song’s final act, Hood unleashes what he once held back. He heaps shame on our current crop of politicians, then sings of a day when “generation lockdown” will vote them out of office—bonus points to Hood for working the word “comeuppance” into a rock and roll song. “Tramp the dirt down, Jesus / You can pray the rod they’ll spare,” he sings, performing what he asks of his fellow Americans—to call down truly righteous wrath and wonder-working power.

Hood’s hellfire and brimstone scorches any American who responds to tragedy from a place of remove.

Christians occupied with the sharpness of Hood’s critique—including a line like “Stick it up your a** with your useless thoughts and prayers”—might overlook the needed challenge he delivers. Indeed, he echoes key insights from the second chapter of James where, in the span of just three verses, the disciple lands just as many punches. First, James sternly warns Christians against using only words in addressing the physical needs of brothers and sisters. Voicing wishes for safety and warmth without buying coats or offering shelter is the equivalent of “useless thoughts and prayers.” In James’ words, “What good is it?” Then, in an overly debated, under-utilized statement, he reminds us that “faith by itself, if it is not accompanied by action, is dead.”

I worry about Christians who don’t instinctively think healing thoughts and offer private lament in the moments after a mass shooting. Hood and his biblical counterpart express their worry for Christians who fail to follow up. We should look for ways to become the answers to our own prayers, they seem to say.

Prayer isn’t useless. It is among the true privileges and powers of the Christian. But we must reckon with what God intends for this spiritual discipline. Prayer responds to the work he has already initiated; prayer aligns our will with his; prayer shapes a holy imagination. If and when we pray, those prayers should carry us out our front doors, into our neighborhoods, to bind and heal, to proclaim good news as we light up the darkness around us. That movement in the world might be personal; it might be political. The nature of individual and corporate sin likely demands both.

Signs of life surround the work of faithful Christians like Shane Claiborne and Taylor Schumann, whose very thoughts and prayers have led them to work for gun reform and on the behalf of shooting survivors. Whether or not you agree with every conclusion, their work is a testimony to the creative brains and compassionate, fleshy hearts God puts within his people. They are living out a liturgy of think, pray, act, repeat. Hearing the call sounded by rock bands, biblical authors, and our peers means bending our thoughts and prayers into usefulness, exercising a living faith that seeks the same peace, safety, and healing on earth that is in heaven.

Topics: Music