Music

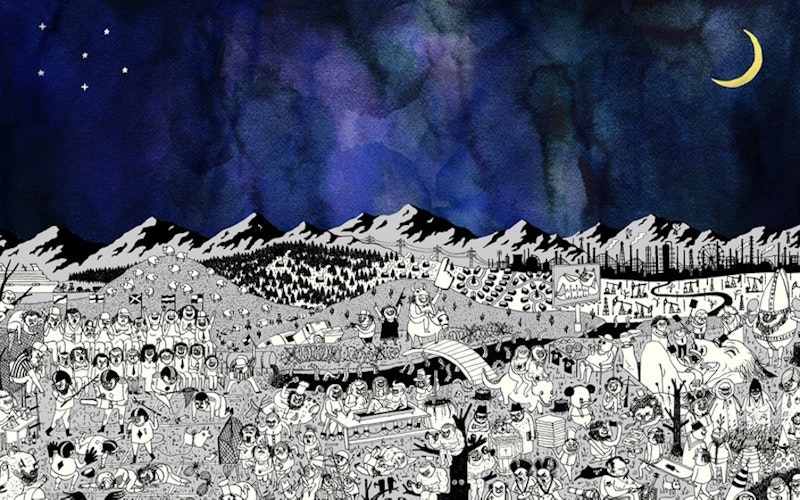

Father John Misty’s Pure Comedy and Other Dark Nights of the Soul

Mother Teresa once confided the following: “I am told God loves me—and yet the reality of darkness & coldness & emptiness is so great that nothing touches my soul.”

Even Mother Teresa experienced a dark night of the soul, a feeling of the silence or absence of God’s presence. Depending on where you are on your faith journey, hearing this might be disturbing. But if you find yourself in a similar place as Mother Teresa, it can be a comfort to hear someone voice their frustrations.

Pure Comedy, the most recent album from Father John Misty, offers a similar experience. In an interview with The New Yorker, Josh Tillman (who uses the stage name Father John Misty) explains that he hopes to be “authentically bogus rather than bogusly authentic.” Layers of sarcasm, nihilism, and sometimes silliness shape his unique musical voice in a way that at times obscures his intentions. Tillman’s stripped-down acoustic style offers a stark platform for his confessions. Sometimes giving in to more elaborate compositions, his vocals ring through in clear and unnerving melodies.

The essay included with the album offers a cynical perspective on the futility of contemporary life. Appropriately, it begins with a quote from Ecclesiastes: "What has been will be; what has been done, that will be done. Nothing is new under the sun! Even the thing of which we say, 'See, this is new!' has already existed in the ages that preceded us."

It may seem like a strange choice to quote Scripture given Tillman’s apparent frustration with religion, as demonstrated on the title track:

Oh, their religions are the best

They worship themselves yet they're totally obsessed

With risen zombies, celestial virgins, magic tricks

These unbelievable outfits

And they get terribly upset

When you question their sacred texts

Written by woman-hating epileptics

Tillman is not the first to appropriate Ecclesiastes for popular music, but his dark sensibilities seem more suitable than the throaty angst of Lorde or the dulcet tones of The Byrds. Like Qoheleth, the narrator in Ecclesiastes, Tillman finds himself in a world in which “all is vanity and a chase after the wind.” The notes of the New American Bible define vanity as “the supreme degree of futility and emptiness.” Pure Comedy is a reflection of those same themes in the age of smartphones and virtual realities. On the title track, Tillman laments:

Their languages just serve to confuse them

Their confusion somehow makes them more sure

They build fortunes poisoning their offspring

And hand out prizes when someone patents the cure

Where did they find these goons they elected to rule them?

What makes these clowns they idolize so remarkable?

These mammals are hell-bent on fashioning new gods

So they can go on being godless animals

This admonition of idolatry feels like a natural extension of the Old Testament prophets, who stood before a wayward people and called them back to God. The second song on Pure Comedy, “Total Entertainment Forever,” is a 1970s-style pop song, a la Tom Jones, about the shallowness of mass media and the entertainment industry. The juxtaposition of form and content here adds to the sense of absurdity, by which Tillman imagines a possible future:

When the historians find us we'll be in our homes

Plugged into our hubs

Skin and bones

A frozen smile on every face

As the stories replay

This must have been a wonderful place

Much of Pure Comedy is dedicated to this pessimistic view of the emptiness of the human experience. Most of the songs feel exhausted, as if written by a man in exile. On “Leaving LA,” Tillman becomes the subject of his investigation:

My first memory of music's

The time at JC Penney's with my mom

The watermelon candy I was choking on

Barbara screaming, "Someone help my son!"

I relive it most times the radio's on

That "tell me lies, sweet little white lies" song

That's when I first saw the comedy won't stop for

Even little boys dying in department stores

Searchers like Tillman can become companions or perhaps guides to each of us on our own spiritual journey, as we find ourselves in a dark night of the soul. Stories of people who seem so sure and confident in their faith, in their vocation, and in their life can be exhausting in those moments, like the bogus authenticity Tillman seeks to avoid. Instead, Ecclesiastes, Mother Theresa, and Father John Misty give us permission to feel this emptiness, to cry out into the void, and to live into that longing for God. For Tillman, that means appreciating life as it is offered to him, as he does on “In Twenty Years or So”:

Oh, I read somewhere

That in twenty years, more or less

This human experiment will reach its violent end

But I look at you as our second drinks arrive

The piano player's playing "This Must Be the Place"

And it's a miracle to be alive

Ecclesiastes offers similar relief: “There is nothing better for mortals than to eat and drink and provide themselves with good things from their toil. Even this, I saw, is from the hand of God.” Human beings cannot know God’s mind or understand all things, but we can recognize God’s grace as it is offered to us in the midst of a chaotic world. For Tillman this world is comedy—infinitely perplexing and frustrating. Yet great comedy, even when born out of despair, manifests as laughter. Pure Comedy reminds us that even as we give voice to darkness and doubt, healing can be found.

Topics: Music, Culture At Large, Arts & Leisure