Music

Hearing Romans 7 in Kendrick Lamar’s DAMN.

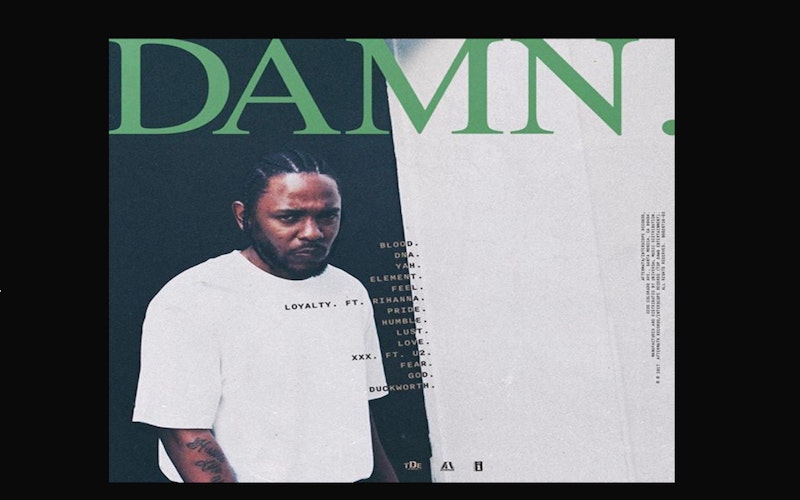

Kendrick Lamar’s much-anticipated new release, DAMN., marked the biggest debut of any album on Billboard this year. Even though every single track from DAMN. is currently on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart, this album, like his last two, must be digested as a whole.

Tracks such as “XXX.,” featuring U2, provide the kind of social commentary that figured prominently on Lamar’s last album, To Pimp A Butterfly. Yet the introspective and self-reflective DAMN. is more of a sequel to his earlier breakout, good kid, m.A.A.d city. Whereas good kid narrated Lamar’s adolescence, culminating in “I’m Dying of Thirst” and praying the sinner’s prayer, DAMN. suggests that a prayer of confession is only the beginning, not the end, of the struggle. The opening to the final track on DAMN., “DUCKWORTH.” (Lamar’s actual last name), underscores the overall shift from social commentary to spiritual autobiography: “It was always me vs. the world / until I found it’s me vs. me.” The album title itself seems to indicate which way Lamar fears the scales are tipping, and there seems to be a sense of helplessness and perhaps inevitability to how this will play out. This internal battle is exacerbated by the constant fear of death, a fear alluded to in the opening track, where we hear Lamar asking a blind woman whether she has lost something, only to hear her respond: “Oh yes, you have lost something. Your life.” The following gunshot drives home the ever-present possibility of unexpected death.

Lamar pairs tracks on the album in ways that highlight this back-and-forth struggle. The slow beat and measured delivery of Lamar on “PRIDE.” underscores our failures and imperfection, while the driving force of the ironically titled “HUMBLE.” underscores Lamar’s success at the top of the rap game. On “LUST.,” the lyrical parallels between verses (Lamar keeps enough of the words identical so that the listener isn’t quite certain whether this is an exact repetition of the previous verse or something different) serve to provide a commentary on the monotony and boredom of a life driven by lust. In stark contrast, the soaring vocals of Zacari feature prominently on “LOVE.,” while Lamar’s repeated “I wanna be with you” serve as a sharp contrast to the repeated purely physical (and sexually explicit) refrain on “LUST.” Taken together, these two tracks artfully capture the beauty of monogamy and the monotony of promiscuity.

DAMN. suggests that a prayer of confession is only the beginning, not the end, of the struggle.

On “FEAR.,” which seems to be the interpretive key for the whole album, Lamar expresses multiple layers of fear: his childhood fear of punishment from his mom; the late-adolescent fear of senseless death all around him; the fear brought on by success, including losing creativity and the criticism of others; and finally, fear of eternal judgment. As with earlier pairs, the following track immediately provides a counterpoint, however, for Lamar’s success has made him like “GOD.,” rich and famous and able to do what he wants. One gets the sense, though, that the invincibility conveyed on this track inevitably leads back to the sense of guilt and fear found throughout the album.

Though DAMN. as a whole leaves us with the sense that Lamar is on the losing end of his internal struggle, the final track, “DUCKWORTH.,” suggests a different possibility. Lamar tells the backstory of how the lives and decisions of two men, his father and his producer, intersected over 30 years ago and then reconnected through Lamar in the present day. Here he underscores both human freedom and responsibility: “You take two strangers / and put 'em in random predicaments / give 'em a soul / so they can make their own choices and live with it.”

So life is within our control? We can make choices and make changes? That would seem to be the conclusion of the matter. However, just as the album ends, Lamar intones, “So I was taking a walk the other day…,” a repetition of the beginning of the album and his chance encounter with the blind woman who fulfills his ultimate fear—death and judgment. Perhaps we are meant to see the blind woman as God, able and willing to demand our life of us at any time for reasons we can’t comprehend.

Musically, DAMN. has less variety than To Pimp A Butterfly, yet lyrically and thematically it further establishes Lamar’s presence as the most compelling rapper at work today. The social and political dimension of To Pimp A Butterfly shines a light on the complex realities of race, violence, and police brutality in America today, matters that most of us would agree need to change. The personal and spiritual dimension of DAMN. reminds us that, much as we long for change in the world around us, it is change within us that is perhaps most elusive and difficult to achieve.

DAMN. leaves us in a place of struggle, fear, and internal tension. It’s a hard place, but a place worth visiting to remind ourselves that as Christians we are simul justus et peccator, simultaneously justified and sinners. Like Paul in his letter to the Romans, we recognize our wretchedness, even as we rest in Christ’s finished work on our behalf to deliver us from our sin and death. Here Lamar (also like Paul), by placing his own struggle front and center, reminds us again of the final outcome of our rebellion apart from Christ: damnation.

Topics: Music, Culture At Large, Arts & Leisure