Music

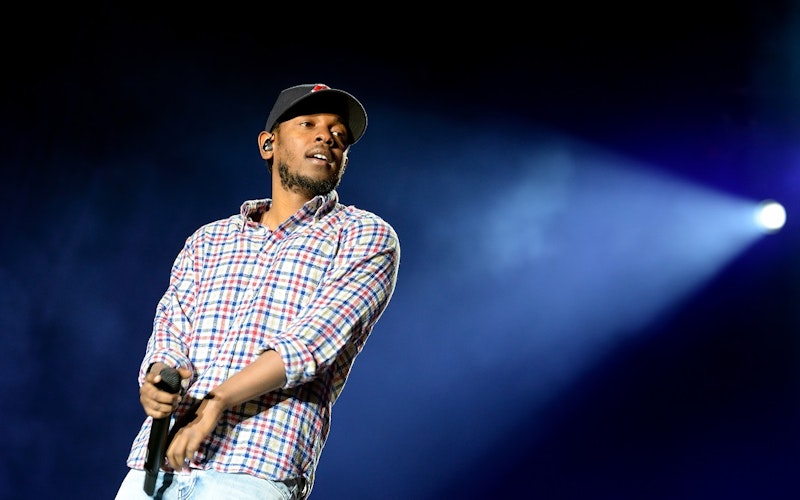

Why White Christians Need to Catch Up with Kendrick Lamar

“I guess I’m running in place trying to make it to church”

This is the last line of verse one, track one from Kendrick Lamar’s surprise album, untitled unmastered. He released it on March 4 without telling anyone. Black America seemed to shout a unanimous “Thank You, Kendrick!” on Black Twitter, at websites like Blavity, and on local radio stations across the country. Lamar, the crowd-anointed speaker for a generation of marginalized millennials, had offered his third major-label take on America and the Black experience. Of course I listened, sharing my take with my church friends and others.

Very few of my non-Black Christian friends knew anything had happened on March 4. Or March 10. Or anytime, including today. Over the past year, I have engaged many non-Black Christians who talk with certainty about the underlying reasons for the social-justice issues referenced in Lamar’s last few albums, as if these Christians had a real-life understanding of Black life in America. They spoke as if understanding Black life did not matter, and that the empathy and action the Bible calls us to are completely possible without being near, or in communion with, the poor and the marginalized. They explained the lapse of understanding that I, and many Black persons, have espoused in our critique and outcry over the police-involved murders of Mike Brown and Freddie Gray; rampant childhood poverty; racial disparities in healthcare; and other evidence of what Lamar illuminates in song after song — that Black life is different in America because we are treated differently under the law and social order. But these Christians spoke without first-hand, personal knowledge. As if their gist of understanding was sufficient to explain the depth of an experience they could never have.

Can we imagine Christ listening to Kendrick Lamar?

Where can that knowledge be found? An easy first step is to find it in art. Kendrick Lamar’s first album, good kid, m.A.A.d city, provides a first-person narrative of the life that leads to death, and how it is processed in the mind of a young Black man — namely, himself. Nina Simone shares her life experience as a Black woman when she sings “Strange Fruit,” “Mississippi Goddamn" and “Four Women.” Michelle Alexander’s interviews about her groundbreaking book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness explore how police interact differently with Black citizens than with white ones, and how poverty and violence is the result. Discussing racial justice without a familiarity with such works is like speaking on Italian art without studying Leonardo da Vinci, or me explaining the specifics of child-rearing as a man without children.

The privileged can request that the sharing of lived experiences of poverty, pain, hunger, incarceration, etc. be delivered on their terms. “No swearing!” “Pull up your pants!” “I read about this, so listen to me explain to you your predicament.” “If you act respectably, then I will listen.” There is no space for the pained to have anger, resentment, or even simply distrust of their abusers.

The reality is that Kendrick Lamar delivers incredible art and insight with untitled unmastered:

Backpedaling Christians settling for forgiveness

Evidence all around us the town is covered in fishes

Ocean water dried out, fire burning more tires out

Tabernacle and city capital turned inside out

Public bathroom, college classroom's been deserted

Another trumpet has sounded off and everyone heard it

(It's happening) no more running from world wars

(It's happening) no more discriminating the poor

(It's happening) no more bad bit***s and real nig**s

Wishing for green and gold the last taste of allure

I swore I seen it vividly

A moniker of war from heaven that play the symphony

But for Christians, or anyone, to hear this they would need to get past the opening of the song:

Come here, girl

Oh, you want me to touch you right there?

Oh, like a little lamb, play in your hair

Oh you want it? Oh you want it right now

Like that? I got you baby

All on you baby

Push it back on daddy

Push it back on daddy baby

And that might be tough. Often, when I suggest secular art as the entry point for Christians to understand social and racial injustices in America, I am met with resistance. “That painting has a nipple.” “The song has cursing!” “The poem talks about lust without repentance.” I ask that you consider something with me for a moment. Can we imagine that Christ might have spent his time deliberately listening to people as they articulated moments of their sin or distress? Can we imagine Christ listening to the Samaritan woman, without him ever demanding that she speak or dress “properly” in order for him to listen? Would Christ ever tolerate coarse language as a means to not only evangelize, but also to understand? Can we imagine him listening to Kendrick Lamar, who speaks of his own demons on To Pimp a Butterfly? Perhaps we think Christ just knew, and never communed. Perhaps. But then again, Christ on Earth modeled the importance of listening and loving into our pain.

Proverbs tells us that “the beginning of wisdom is this: Get wisdom. Though it cost all you have, get understanding.” The segregated church must make time to study its distance, privileges, and opportunities. Christians must take the time to actively listen, consider, respectfully question, and align their lives to the marginalized, in order to understand the immediacy of the poverty which can drive the unfortunate actions of those seeking to survive this country’s apathy. This is more than volunteering on the weekends. This is living in communion. This may not be you, your church, your friends or your reality. But it represents the experiences of far too many in our country and churches. The wisdom is in the streets, below the surface, and across town. To hear the words of Kendrick Lamar is to take a step into communion with the reality of Black life in America. Church, get wisdom. Listen.

Topics: Music