Arts & Leisure

Moord Velden: Portraits of Christians Caught in Chicago’s Crossfire

Editor’s note: This is adapted from Keri Wyatt Kent’s introduction to the Moord Velden project. The full text and all of photographer Michael VanDerAa’s images can be found here.

moord (plural moorden, diminutive moordje n)

1. murder

velden (plural form of veld n)

1. fields

An area just under five square miles bordered by two major expressways on Chicago’s south side, Roseland was originally a Dutch enclave, settled in the 1840s. Today, it is a place without much reason for hope. In Roseland, everyone knows someone who’s been shot. In many cases, it is their own family members. Mothers and grandmothers mourn the loss of children, gunned down outside their own homes. It’s a dangerous place.

Why are these things happening? Why does Chicago suffer from so much gun violence, particularly in neighborhoods like Roseland? Where are the guns coming from? Why do even young children settle their disputes with guns, especially when Chicago has strict gun laws? When people are sent to prison, do they come back reformed, or just better at being criminals? Does the threat of incarceration or even being killed stem the violence, or just make people more desperate?

There are huge, complicated, systemic issues involved: poverty, drugs, unemployment, inferior schools, racism, corruption in the criminal justice system, parenting issues, family breakdown. There are no easy answers to the violence. It is a tangled, complex problem that seems to be getting worse.

These incredibly difficult questions raise even deeper ones: have we lost hope? Should we simply give up? Can anyone do anything to make a difference? Can Roseland change? What will bring healing and restoration to this community?

In the middle of this violent neighborhood stands a beacon of hope.

In the middle of this violent neighborhood, at 108th and Michigan Avenue, stands a solid brick building: Roseland Christian Ministries, a beacon of hope in the neighborhood. The ministry runs a women’s shelter and a food pantry. Children from the neighborhood show up after school to play basketball in the gym and attend tutoring sessions. There are also meals provided for the community, including a daily lunch.

Other initiatives include a free day camp for younger children during the summer. There are also youth arts programs, Bible studies, and more. The Men of Honor program, for example, mentors and guides young men ages 13 to 18 and challenges them to live at a higher standard than the culture around them.

There are no easy answers to the questions, no simple solutions to the incredibly complex problems. However, nearly all of the people we interviewed have found something else inside this big brick building. Here, they know that they are not alone. Here, in the midst of the pain and struggle, they find encouragement, friendship, support, strength, faith, and yes, even hope. It’s a beautiful picture.

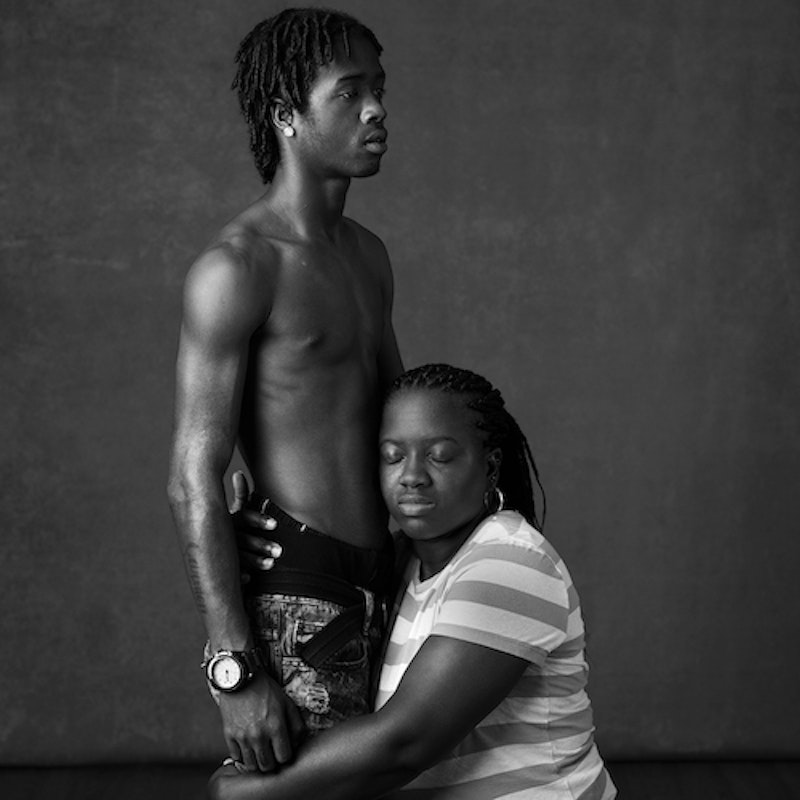

Kamari Pleasant, Kisha Pleasant

As he walked home late one night in 2015, Kamari Pleasant heard a car in the street behind him. He had reached his front porch when bullets started flying.

The 16-year-old took off running, and his mother, Kisha, awakened by the sound of gunshots, grabbed her phone and called her son. “Where are you? Where are you?” she asked. He told her he thought he’d been shot, and to open the front door.

A moment later, Kamari ran down the street and into the house. He had a burn mark on his arm where a bullet had grazed it, but thankfully he’d escaped without any other injury.

Who was it, his mother demanded to know. He said he didn’t know, that he hadn’t had any problems with anyone

“They come around frequently, just shooting,” Kisha says. “Unfortunately, it’s normal for people to come and just shoot.” Sadly, you don't have to be in a gang to become a target, and the motive for shooting can be based on which block you live on or who you hang out with, she adds.

A week later, Kamari was leaving a gym where he’d been playing basketball with friends. Suddenly, a car pulled up and started shooting. He and his friends ran, first away from the gym, then back into it. Kamari could feel a sharp pain in his foot. When he got inside, a total stranger carried him to the bleachers. He discovered that as he ran, a bullet had bounced off the sidewalk, piercing the bottom of his shoe, and gone through his foot.

Thankfully, Kamari survived both incidents. Because he went to the emergency room for treatment of his foot, the crime was reported, but no one has been charged. Kamari had no idea who was shooting at him. After the shootings, Kamari stayed at home, not even wanting to go outside. But lately, he’s begun hanging out with friends again, his mother says. She frowns, smoothes her hair. “He wants to go to people’s house, one of his friends has a car… I just keep praying.”

Kisha moved to Roseland with her family when she was 7 and grew up here. She moved away because of the violence in 2004, while still attending church at Roseland Christian Ministries. She found a small apartment in Blue Island, a less violent area not too far away. Rents are higher in Blue Island, so the apartment she and her children shared was small. In 2011, she considered a move to DeKalb, where low-income housing was available and she would have much more space.

Joe Huizenga, pastor at Roseland Christian Reformed Church, suggested she join the Homes Program of Roseland Christian Ministries, a revitalization initiative which buys boarded-up houses within the neighborhood and rehabs them, allowing families to earn sweat equity by helping with the rehab, then work toward owning the home. She lives there with her three children and her mother.

It has not been easy, though. She recalls feeling “scared and traumatized” coming back to Roseland and remembers going out one morning to find all of the windows of her car shot out. “I’d heard that my house used to be a house where drugs were sold,” she said.

She works at Roseland Christian Ministries as an administrative assistant. At times she feels conflicted about staying in Roseland—wanting to keep her children safe, but also wanting to be an influence for good in the troubled neighborhood.

“I keep praying,” she says. “I’m not hopeless. I'm happy, blessed, and God is definitely watching over all of us. I do think things can change. We have to be willing to reach out and connect with those who are doing the shooting. They don't know any better and they need love and guidance too. My spirits are up and I'm smiling everyday because he woke me up this morning, I can talk, walk, and sing!” Referring to Roseland Christian Ministries, she adds, "This building is a safe haven."

Topics: Culture At Large, Arts & Leisure, Art, Theology & The Church, The Church, News & Politics, Justice