Movies

Movies Are Prayers

My first article for Think Christian was a fumbling attempt to ask if a pair of grim movie heroes from 2008—Batman of The Dark Knight and James Bond of Quantum of Solace—were worthy representatives of the biblical notion of righteous anger. I’m not sure I offered a good answer (or even phrased the question in a compelling way), as the piece was an early attempt to bring explicitly Christian reflection to my film criticism.

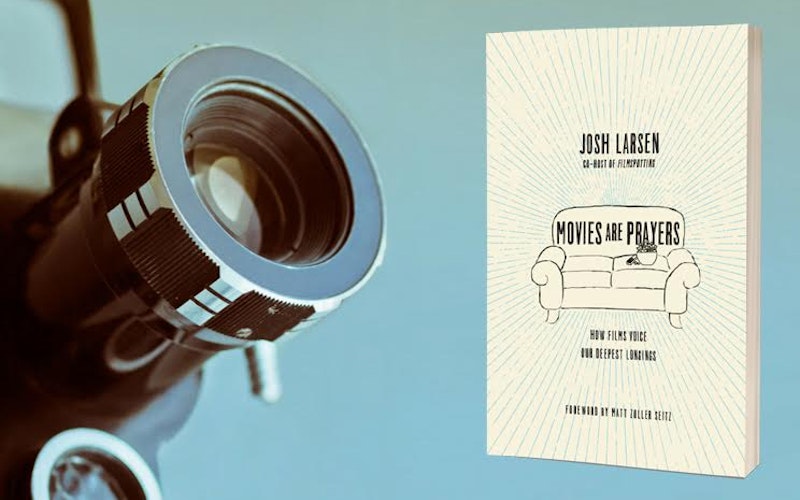

On June 13 InterVarsity Press will publish my first book, Movies Are Prayers, which hopefully reflects greater aptitude for such a task than that first TC article. I had the germ of the idea for this book back in 2008, but was in no way qualified to write it. I needed a few more years to figure out what it meant to write about movies through the lens of my faith. After becoming editor of Think Christian in 2011 I was able to learn on the job, exploring alongside other contributors what it means to think Christianly about contemporary culture, including the films we watch.

Movies Are Prayers certainly isn’t the final word on how to do this in relation to the cinema. But it’s my best attempt yet, in which I explore the idea that prayer can be expressed by anyone and can take place everywhere, even in movie theaters. I examine dozens of seemingly secular films, revealing how—in both form and theme—they function as various forms of Christian prayer: praise, lament, anger, confession, and more. Here’s an excerpt, in which I suggest that Field of Dreams can be seen as a prayer of obedience:

It is popular cinema’s most familiar command, perhaps even more so than Charlton Heston’s Moses demanding, “Let my people go!” Standing in his corn field, surrounded by lush green leaves and the warm embrace of an early evening sun, Ray Kinsella (Kevin Costner) hears a whisper: “If you build it, he will come.”

Field of Dreams, in which Iowa stands in for heaven, depicts one man’s spiritual journey of prayerful obedience. Given a vision of a baseball diamond, Ray decides to build a full-scale field on his farm, complete with bleachers and lights. Doing so is a considerable sacrifice, considering corn could be grown on the land, yet Ray obeys. “I have just created something totally illogical,” he says, surveying the perfectly manicured grass and straight white lines with a grin. His neighbors aren’t as amused, and their disdain is a reminder that Christian obedience often doesn’t make sense to an outside world that operates on a different set of rules.

Prayer can be expressed by anyone and can take place everywhere, even in movie theaters.

Eventually, someone does come: Shoeless Joe Jackson himself (Ray Liotta), along with a number of other players who were banned from baseball after being accused of throwing the 1919 World Series. Having been stuck in some sort of purgatory, they find freedom on Ray’s field, able to play their beloved sport once again. Director Phil Alden Robinson lends a hushed holiness to these scenes, as the men reverently toss a ball back and forth under the soft glow of the field’s lights, a deepening dusk rising from the surrounding cornfields. It’s a magical moment. Even if you don’t care a bit for baseball (and I gave up the game around age ten, when it consisted of long lonely stretches in right field and being beaned at the plate by errant, pip-squeak pitchers) Field of Dreams makes you feel what one character describes as “the thrill of the grass."

Later in the film, Ray receives other commands: “Ease his pain.” “Go the distance.” Following each one leads to a certain peace for others, as happened with Shoeless Joe, while Ray plays the part of accidental guru. As the bills pile up and the potential farmland remains unused, though, he begins to wonder if he should have left well enough alone—if it was worth putting his farm and family at risk. It comes to a boiling point when he asks Shoeless Joe if he can go with the players into the cornfield, to see what lies beyond, but is told that he’s not invited. “I have done everything I’ve been asked to do,” Ray responds in exasperation. “I didn’t understand it, but I’ve done it. Now, I haven’t asked what’s in it for me. . . . [But] what’s in it for me?”

“Is that why you did this?” Joe responds. “For you?”

Obedience doesn’t work like a rigged slot machine, though, where you put your acts of observance in and a reward comes spitting out. It is, instead, an expression of living within the reward you’ve already been freely given. In the Heidelberg Catechism, question 86 asks the same thing Ray does—“Why then should we do good works?”—and offers a four-part answer: “So that with our whole lives we may show that we are thankful to God for his benefits, so that he may be praised through us, so that we may be assured of our faith by its fruits, and so that by our godly living our neighbors may be won over to Christ.” By following the voice, building the field, welcoming the Black Sox, and enriching the lives of others, Ray Kinsella goes four for four.

Now that the book is actually something I can hold in my hands, I feel particularly grateful to the folks at TC’s parent ministry, ReFrame Media, who have given me the venue to explore faith and film in this way over the past number of years. And I’m also thankful for the many TC readers and commenters who have accompanied me on this journey. Let’s keep the conversation going with Movies Are Prayers.

Topics: Movies, Culture At Large, Arts & Leisure