Culture At Large

Remembering the Eucatastrophe of Richard Adams’ Watership Down

Before I write these lines, I make eye contact with my rabbit. He sits on a shelf looking down at my desk, ears open like radar dishes. He’s a ceramic figurine in the likeness of Dandelion, keeper and teller of stories for the rabbits of Watership Down. In this beloved adventure novel from Richard Adams, Dandelion’s stories of the trickster called El-Ahrairah provide a sense of identity, purpose, and inspiration for troubled creatures.

That’s also what Watership Down does for me. I have a renewed sense of identity, purpose, and inspiration whenever I revisit the book. What The Chronicles of Narnia and The Lord of the Rings are for so many, Watership Down is for me: a story that makes sense of the world, that gives me a vocabulary for loss and grief, that rekindles my longings for what is best, and that helps me overcome my fears.

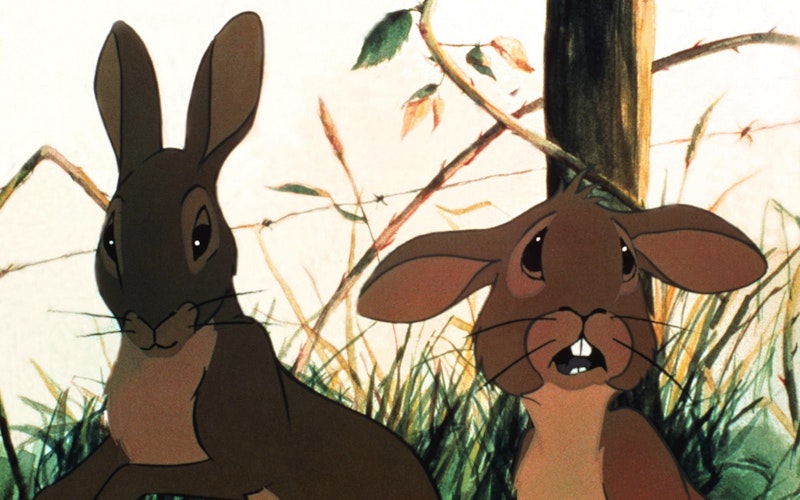

The story is best on the page. The Criterion Collection’s recent restoration of the exquisite 1979 animated film is an impressive distillation, and another film version is on the way, but I feel some urgency in recommending the source material, with its inimitable complexity and richness, to a new generation.

Adams, who died Dec. 24 at the age of 96, first imagined Watership Down as a way to entertain his daughters during a road trip. The narrative grew into a novel beloved by generations and influential in countless creative works (including my own fantasy series). Whenever I open my timeworn copy, I’m reminded of why it has commanded my attention since I was 10. It was so much more frightening, dire, and—for lack of a better word—realistic than anything else I’d read. While Watership Down is a story of talking rabbits, it isn’t a cute nursery story about bunnies. It’s a substantial literary achievement, one as rich in philosophical and political subtext as it is thick with literary allusions. It deserves serious critical attention, including theological exegesis. (Stanley Hauerwas strikes gold with his brilliant interpretation in A Community of Character.)

Watership Down deserves serious critical attention, including theological exegesis.

As we follow a company of anxious rabbits who flee their endangered warren in southern England in hopes of finding an ideal home, we encounter dangers in the elements, in natural predators, and in the oblivious industry of humankind. But the story’s most fearsome chapters involve the dangers of other rabbits—some who are duped into false security by devious humans who spoil them and some who adhere to the rabbit equivalent of a fascist regime.

Here are a few specific reasons I find Adams’s tale so richly rewarding in the religious sense.

- The rabbits’ mythic hero, El-Ahrairah the “Prince of Rabbits,” is in constant dialogue with his Maker. Though Frith the Sun God delivers judgment for the trickster’s disobedience, he also loves him and delights in his creativity and cleverness.

- Fiver, the rabbits’ reluctant prophet, warns those with rabbit-ears to hear of pending doom. And his anticipation of a paradise—“a high, lonely place with dry soil, where rabbits can see and hear all round and men hardly ever come”—motivates a community to risk their security for a better future, even as it stirs our own longings for an Eden we were meant to inhabit.

- Adams is unsentimental. Rabbits die bloody deaths at the claws and teeth of their enemies. Hope is substantial only in the full acknowledgment of evil and death, and it is realized by moving through darkness.

- While Watership Down’s story is set in motion by human arrogance—a plot to “develop” a territory that is teeming with life—its climax is redeemed by the compassionate impulse of a little girl who cares for the little things.

- When Hazel, the rabbits’ humble and reluctant leader, sprints across the English countryside to save his people, he prays to his mythical god. And for one fleeting moment, like Christ in Gethsemane, he gets an answer. It’s not the easy answer he wants, but it’s the truth. And in that moment, myth and history converge. This is what Tolkien called “eucatastrophe”: a unique contribution of fairy tales to human experience. The fairy tale, Tolkien argued, allows us to express a deep intuition of what will be revealed: a happy ending. Or—as he put it in his essay “On Fairy-Stories”—“a piercing glimpse of joy” that “rends indeed the very web of story, and lets a gleam come through.”

That “gleam” of revelation—that’s the glint I see in the eye of the ceramic figurine of Dandelion, my icon. Adams’ characters have become so essential to my imagination that they seem as alive and inspiring to me as figures from my own history.

That is why Watership Down, a story of such humble beginnings, seems like a miraculous achievement. To mark the passing of its inspired storyteller, I recommend that you discover—or, with me, rediscover—every page.

Topics: Culture At Large, Arts & Leisure, Books