TV

The Office's St. Bernard and Our God of Second Chances

In the sitcom universe, where characters are often reduced to a catchphrase, Andy Bernard feels like a revelation.

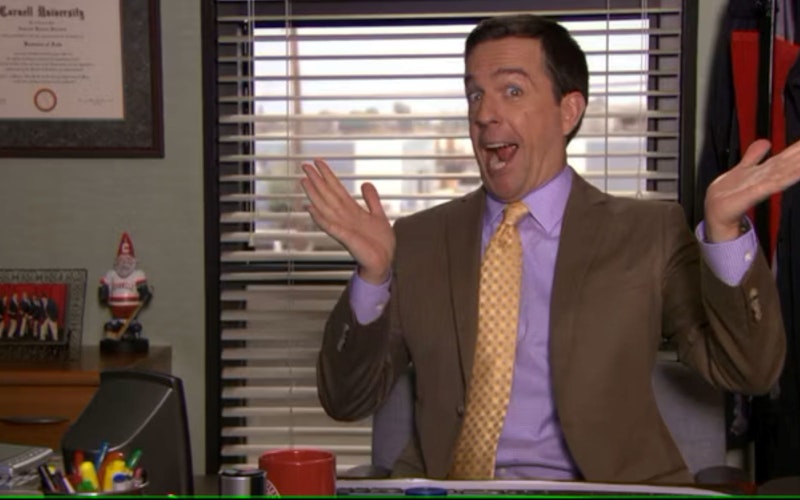

Played by the nimble Ed Helms, Andy arrives in Season 3 of The Office, as the show’s world has tilted off its axis. Jim and Pam’s will-they, won’t-they romance seems to have settled on won’t-they, with Jim’s transfer to Dunder Mifflin’s Stamford, Conn., branch. There he encounters his new foil, Andy, a salesman with an Ivy League education and overactive ambition gland.

At first, Andy doesn’t even register as a character you love to hate. The show has fun at his expense but never sketches in the humanity that makes the rest of The Office’s motley crew sympathetic. By the time Jim (John Krasinski) places his personal effects in Jell-O, Andy entrenches himself as an even more humorless version of Dwight (Rainn Wilson). Yet much to the viewers’ surprise, over the next six seasons, Andy carves a path not unlike the road a new Christian walks. Going “the whole nine ’Nards,” he stops living for himself and dying for approval and learns to depend on grace.

When the Scranton and Stamford offices merge, Andy can’t help but jockey for position. It’s what he does. The secrets to the success he hopes for are “name repetition, personality mirroring, and never breaking off a handshake.” An early bond with Michael (Steve Carell) is built on sand when, to the viewers’ delight, the king of oblivion eventually (and ironically) wearies of Andy’s lack of self-awareness. “Who’s that sportscaster that bit that lady? Marv Something?” Michael says in “The Return.” “Andy is like Marv Something—great sportscaster. Big weirdo creep.”

Spiraling as his plans come undone, Andy punches a hole in a wall and finds himself shipped off to anger management. That he initially spins his exile as “management training” shows his failure to reckon with the depth of his sin. Anger is the worm-eaten fruit of his condition, but his lust for approval and need to save face reminds us that even when our behaviors are in order, our hearts betray us. Redemption is the only remedy for our soul-sickness, the only force powerful enough to heal us from the inside out.

When Andy returns to Dunder Mifflin, he receives no prodigal’s welcome; rather, he wears a pariah’s hairshirt. At first, a newborn deer slipping with every footfall, he settles into his fresh start and finds Scranton the site of daily second chances. Eventually, Andy encounters something resembling the rebirth Christians experience.

Our salvation comes all at once, yet little by little. Anyone in Christ is a new creation. Still, personalities remain, waiting to be transformed into their truest version. Andy remains a little needy and overeager, something of a preppy people-pleaser. Yet rather than use these traits to suit himself, he increasingly spends himself for the common good. Rather than waste every waking moment plotting to make himself look good, he gradually seeks to exalt his co-workers and make their lives better.

Through the refining fire of trial and experience comes gold. The pain of being cheated on spurs Andy to confront Michael and urge him to end an affair with a married woman. He rejects the ways of his blue-blood brood—who own a history of silencing whistleblowers—to cry foul when the company’s printers pose a safety risk.

Andy remains a little needy and overeager, something of a preppy people-pleaser. Yet rather than use these traits to suit himself, he increasingly spends himself for the common good.

Andy’s mettle passes the test when Michael leaves The Office and the manager’s chair is up for grabs. When it appears Will Ferrell’s Deangelo will step into the role, Andy goes to humiliating lengths to please him, yet seems to understand there’s something wrong with the way the new boss treats him. Mistreatment wouldn’t even register to the old Andy Bernard, the one who just moved from Stamford to Scranton; it simply would be the price of doing business.

When the job opens again and Andy puts himself in contention, he exhibits something resembling humility, calling himself “a safe, if not slightly unexciting choice.” The old Andy would’ve talked up his credentials and made unsavory maneuvers. The new, improved Andy makes his case on his rapport with his co-workers and his willingness to support the status quo they all appreciate.

Landing the gig, Andy struggles to shed his approval-seeking skin, fishing for compliments and looking for “attaboys” from new CEO Robert California (James Spader). But when California divides the office into winners and losers, Andy—who once saw winning as the only thing—extols the virtues of his co-workers and amplifies the need for a ragtag, interdependent workplace, coloring with shades of Paul’s commendation of the body of Christ.

Andy, like the rest of us, remains a work in progress. He strings Erin (Ellie Kemper) along, sometimes neglecting her. His interest in fame and drama overshadows his good judgment. But he nearly always comes around to the right side of the situation and, embracing a new default mode, exhibits consistent concern for his fellow employees. Once competitors, they become his friends—and a more functional family than the Bernards ever have been to him.

Near the end of Season 8, in “Angry Andy,” his job is stolen out from underneath him by the scheming Nellie (Catherine Tate) and sinfully ambivalent Robert. Andy lands another punch in the same spot, once again busting up innocent drywall. What might seem like a failure of character or a sign the man never changed at all, takes on new resonance. This time, Andy’s anger is much closer to the righteous side of the spectrum. These bookend experiences become like biblical Ebenezers—markers of where he’s been and how far he’s come.

Late in the series’ run, Andy’s co-workers extend special moments of grace. Recognizing the damage done by an emotionally withholding father, they transform a disastrous “Garden Party” into a moment of solidarity. Watching Andy trip over his two left feet for business at “Gettysburg,” Jim and Darryl (Craig Robinson) remind him that the Dunder Mifflin crew is on his side and will follow him just because he’s Andy.

These episodes stand out, yet they are the rule rather than the exception. Reflecting on the years with the employees of Dunder Mifflin, we recognize a steadfast dynamic. Show up every day for work trying to be yourself and a simple 9-to-5 love emerges to cover a multitude of sins.

Watching Andy stop holding his breath for some skewed version of the American Dream, bearing witness as he relaxes into this environment, delivers its own sense of sweetness and self-assurance. His character arc reminds us that, no matter how much we lost in the Garden of Eden, the chance to be known and loved is still possible and worth seizing.

When Andy sees this, he finally fulfills his destiny, spoken as a humorous aside by Michael on the day the two branches merged: “Andy Bernard. St. Bernard.” The God who gives second chances makes saints of us. With heaven and a halo reserved, we stumble our way through becoming who we are. But we never run the risk of imposing on God’s goodness or draining his reservoir of redemption dry. With our ultimate restoration paid in full, he continues to give out modest reminders, everyday second chances—until the day when second chances are no longer necessary.

This article was originally published in 2019 as part of our Theology of The Office ebook.

_______________

At Think Christian, we encourage careful cultural discernment. We recognize and respect that many Christians choose not to engage with pop culture that contains particular content, such as abuse, sex, violence, alcohol or drug use, or that employs the use of coarse language. To that end, we suggest visiting Common Sense Media for detailed information regarding the content of the particular pieces of pop culture discussed in this article.

Topics: TV