Movies

The Card Counter and Flannery O’Connor

Has the thrill of gambling ever felt as deadened as it does in The Card Counter?

William Tell (Oscar Isaac) motors around from casino to casino, wandering through the gray conference halls and brown bathrooms and yellowing motels to make a modest living off blackjack and poker. Victorious hands are rarely shown; rarer still any spark in William’s eyes. But that’s by design, because writer-director Paul Schrader’s latest film resists the glamour typical to most gambling movies, focusing instead on dull routine.

For William, gambling is a routine, and thus a rescue. By his own testimony, he’s a man “suited to incarceration”—an apt description in more ways than one. After serving a prison sentence for committing horrendous acts, William takes up gambling as a way to enforce a structure of rules: the rote probabilities of hands dealt and the laws of chance become his mundane mode of existence.

Of course, as much as he tries to move past his crimes, they plague him continually. Schrader saves the most garish filmmaking moments for these flashbacks, distorting the image with an extreme fish-eye-lens effect and blaring heavy metal. As William blankets his motel furniture in white sheets, it sinks in: the most vibrant parts of William are his searing memories, so his only recourse is to dull his life as much as he can.

Eventually, William meets La Linda (Tiffany Haddish), a high-stakes backer with whom he begins a tentative friendship, and Cirk (Tye Sheridan), a young man on the cusp of his own irrevocable decision. As these friendships grow, they offer William what may just be his last chance for normalcy. And, in Cirk specifically, a chance to rescue a life and do the right thing.

With The Card Counter, Schrader is focused on many of the same themes as his last film, the much-praised First Reformed, though he views them through a different facet. Both films wonder at the chance for redemption in a world so marred by evil. Beyond mere personal guilt, they both consider the institutional failures that all but guarantee evil’s recurrence. In First Reformed, it was our societal failure to attend to our environment that pushed the main character, Reverend Toller (Ethan Hawke), into the bleakest extremes of radicalism and self-punishment. The specter that haunts The Card Counter is the United States’ dehumanizing use of torture at Abu Ghraib.

First Reformed was a carefully crafted homage to Schrader’s inspirations: filmmakers like Robert Bresson, Ingmar Bergman, and Yasujiro Ozu. While The Card Counter bears its own nods to these filmmakers—William’s mundane, constant routines of incarceration echo Bresson’s masterpiece of resistance, A Man Escaped—it also embodies the spirit of a very different artist: Flannery O’Connor.

The Card Counter wonders at the chance for redemption in a world so marred by evil.

The short stories and novels of Catholic author Flannery O’Connor have allured and repulsed readers since their publication. Or both at once, as Jeff Reimer described at Comment: “I saw then in the macabre grotesquerie of her stories a spiritual incandescence and insight.” O’Connor’s stories were frequently set in a landscape of moral rot and religious pretense: roaming murderers, selfish misanthropes, hypocritical church ladies, old men lost in pride, hate and cruelty in every eye. But against this backdrop, O’Connor cast a faint outline of grace.

Schrader’s recent work is cut from a similarly bleak cloth. Much like O’Connor’s stories, Schrader’s films are intensely difficult encounters. His characters trade in torture, terrorism, and self-flagellation. They wrestle with doubt. They lose hope. They surrender to their worst impulses. They turn to devastating actions. They are not good men. But even amid stories weighed down with darkness, Schrader’s work, like O’Connor’s, remains haunted by Christ.

As William strives to save Cirk, he laments the “weight created by past actions,” noting how it parallels the debt accrued by reckless gambling. He wonders in his journal, “Is there an end to punishment?” He means it in the sense of a limit, although to question the purpose would be equally significant. Even when he seeks redemption, he reverts to pursuing it through his narrow, violent skill set. Punishment and judgment are the only things that can help William understand his life, but they never seem sufficient. They’re never enough and they never provide what he’s searching for.

In the end, Schrader subverts William’s attempts at redemption. As with First Reformed, he does so with generosity, but The Card Counter lacks the previous film’s subtler qualities. The script here is more heavy-handed; the score throughout is moody to the point of feeling overbearing. Thus, with the resolution, what was ambiguous and controversial in First Reformed here seems obvious—even held as the credits roll.

Still, the movie’s revelation is a potent one: that these condemned characters can’t redeem themselves. Redemption cannot be achieved finally through action; it must come as a prodigal gift. Reverend Toller and William Tell both, at the end of themselves, run headlong into an unexpected encounter with grace.

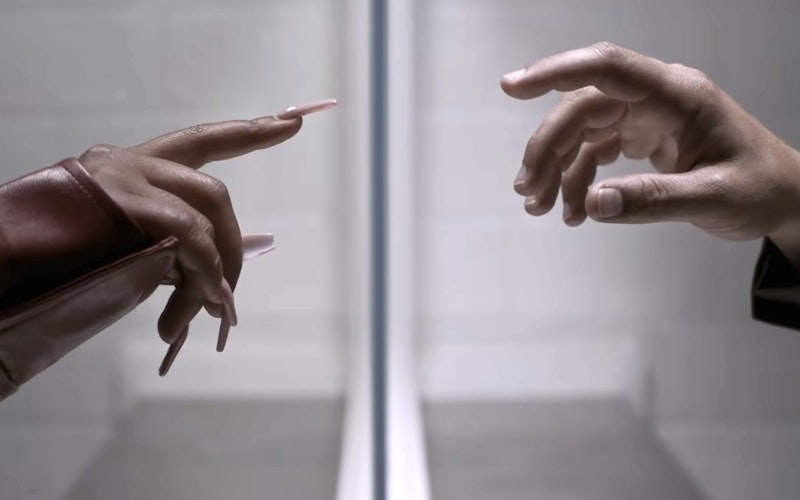

This is the heart of Schrader’s recent films. Despite being shrouded in the worst evil that humanity can conjure, a flame of grace still burns through the dark. As in the grim tales of Flannery O’Connor, it can be found there in the negative space, hovering over the scene, watching the characters fail. To the shock of all, in the gentlest of touches, grace then enters in—an image of the lavish, mysterious grace of Christ.

Topics: Movies