TV

The Hermeneutic Challenge of CBS’ Living Biblically

Almost 10 years ago, A. J. Jacobs’ book Year of Living Biblically was published. Having grown up in a secular family, Jacobs chronicled his year-long journey of following the commands of the Bible, raising interpretive questions and eyebrows along the way. That journey is now being translated into a sitcom, Living Biblically, which premieres tonight on CBS.

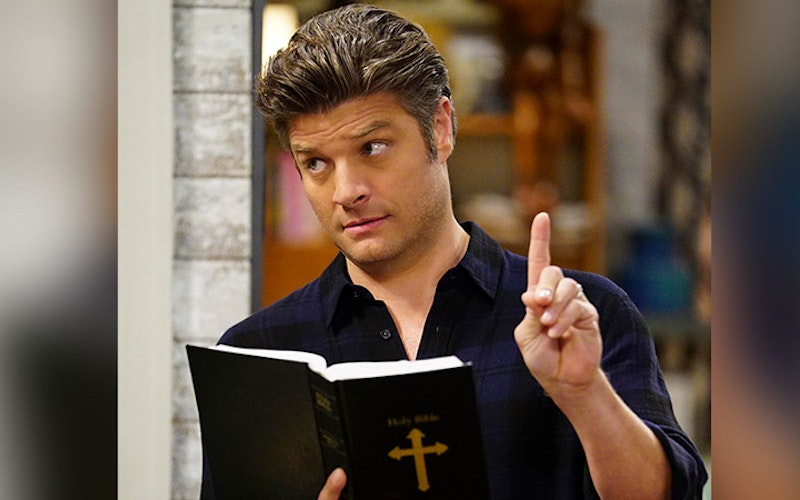

The show follows the basic contour and storyline of the book. Provoked into crisis by the death of his best friend and his wife’s announcement that they are expecting a child, Chip (Jay R. Ferguson) decides that he needs to look to the Bible for how to live his life. His wife is a skeptic, but supportive so long as this journey helps Chip become a better man. Drawing on the support of his “God Squad”—a priest and rabbi and yes, they walk into a bar—Chip tries to navigate questions of faith in the modern world.

So what exactly does it mean to live “biblically”? The first episode answers this a bit simplistically, as when Chip throws a small rock at the head of an adulterous co-worker in order to follow the letter of the Mosaic law. Though it makes for good comedy, Chip’s initial application and interpretation of Scripture come off a bit naive, unaware of how Jesus himself handled a similar situation.

Later episodes, however, do highlight a more complex take on what it means to live biblically in the modern world. When engaging the question of idolatry, Chip is attuned to the way in which his smartphone functions as an idol. Having smashed his phone in a Moses-like fit of rage, he dons a fanny pack in a futile attempt to replace all the functions of his smartphone. Fanny packs aside, this episode presents a more nuanced way of reading Scripture, of understanding not only the message it contained for the original audience, but thinking through what it means to be people shaped by that text in today’s context.

The show also deals with the question of faith in an era of unbelief. The second episode finds Chip navigating the question of prayer. After a significant prayer is answered, his unbelieving wife and science-minded mother-in-law have different takes on how to interpret Chip’s apparently successful prayers. The show helpfully displays the way both positions put a question mark to the other. That is, not only is the believer haunted by the possibility of doubt, but the skeptics are also haunted by the possibility of belief, that maybe there is in fact something going on. At least in this episode, it seems that the show fairly represents the reality of our secular age, in which, as James K.A. Smith puts it, “Faith is the doubter’s doubt.”

Not only is the believer haunted by the possibility of doubt, but the skeptics are haunted by the possibility of belief.

As the show moves forward, I’ll be interested in seeing how it wrestles with the interpretation and application of the Bible. The subtitle of Jacobs’ book promises he will “follow the Bible as literally as possible.” By “literally,” Jacobs apparently means without reference to the history or culture of the original biblical text, without reference to how other texts within the Bible may speak to the same topic, and without criteria for how we ought to move faithfully from what the Bible says in an ancient culture and context into our culture and context. To be fair, this is how many North American Christians read their Bible—with reference first and foremost to their own lives in a way that ends up cherry-picking from the text. But this misses out on good biblical interpretation and application, which pays close attention to questions of historical and cultural context and the broader context of the canon of Scripture.

Perhaps a deeper theological danger is that this view of “living biblically” makes the Bible all about us. In other words, it becomes all law and no gospel; it’s about what we can do for God rather than about what God in Christ has done for us. The end goal, then, is not the glory of God because of God’s amazing work of redemption. Rather, the goal is my self-improvement and fulfillment. This comes through in the show’s emphasis on how Chip just wants to be “a better man.” God and the Bible are useful insofar as they are helpful to me in my journey. As a result, I end up instrumentalizing God and Scripture, turning them into one more therapy to help me grow to become a better me. Who could object to that? Certainly not Chip’s wife, who seems amenable to this project so long as it’s conceived under this therapeutic rubric of maximizing self-growth and development. But what if Chip follows the Bible and it ends up in him being “worse,” at least by the standards of his wife and the surrounding culture?

This questions points to the challenge for Christians who want to live biblically in the right way. The point is not to scandalize because we cherry-pick commands from an outdated book. Instead, we should follow Jesus in a way that leads us to embody faith in an age of unbelief, hope in an age of despair, and love in an age of polarization. In other words, we need to make people think we’re strange for all the right reasons. That’s living biblically.

Topics: TV