Movies

The Invisible Man (in the Sky)

Whenever I did something bad as a kid, I saw this clear mental image of God watching me at all times, making a mark on a chalkboard next to my name. No one taught me this image. I was a faithful Sunday school student (I got mad when we visited my grandparents' church because I would miss qualifying for our church's perfect attendance award), but I'm certain my teachers never instilled such an image in my mind. And while I did have one school teacher who wrote our names on the chalkboard as a disciplinary measure, he never connected his classroom management to divine record keeping.

Where did my imaginary, heavenly chalkboard come from, then? It was the creation of my subconscious, an amalgam of real-world discipline I had observed, and the image(s) of God I was learning from my faith community.

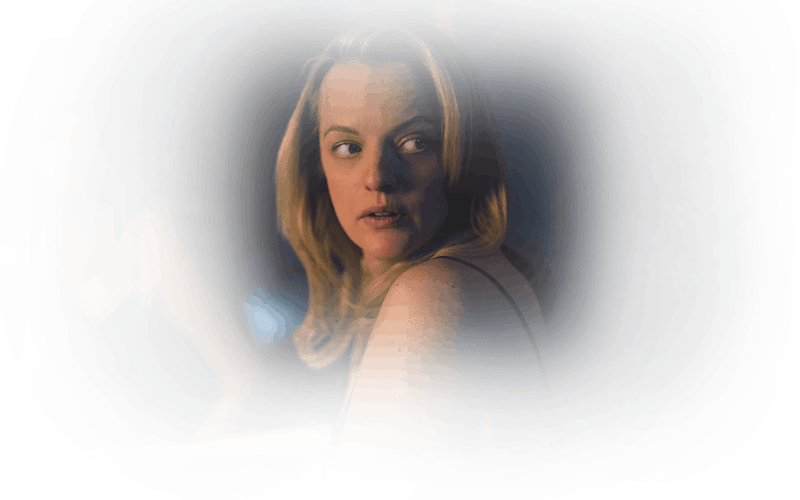

I hadn't thought about that heavenly chalkboard in years, until I watched Cecilia Kass (Elisabeth Moss) shouting at an empty room in The Invisible Man. Directed by Leigh Whannell, the movie updates a horror classic with a simple twist: the protagonist is not Adrian Griffin, the titular transparent man, but Cecilia, his abused partner. (Slight spoilers ahead.) After escaping from Adrian's compound in the opening sequence of the film, Cecilia is told that Adrian has died by suicide and she has inherited a substantial sum. But almost immediately, she is tormented by an unseen force.

Whannell cleverly leaves the camera to linger on empty rooms so we can see the mischief unfold. While Cecilia's allies are (understandably) worried about her mental stability, we viewers know what she knows: Adrian is still alive, somehow invisible, and tormenting her.

Much of the meat of the film involves Cecilia alternating between feeling fearful and furious, between fleeing or facing her stalker. But since that stalker is invisible, we watch Cecilia acting against an empty room. Whannell rests his story squarely on Moss' more-than-capable shoulders; she is a powerhouse, conveying an impossible mixture of emotions. Cecilia is a woman who needs to be believed, but knows she won't be. The Invisible Man is being hailed (rightly) as a horror film for the #MeToo movement—its tagline could have been #BelieveWomen.

Whannell cleverly leaves the camera to linger on empty rooms so we can see the mischief unfold.

In his landmark book, Discipline and Punish, Michel Foucault employs the design of a prison called a Panopticon to illustrate how power can become abusive. A Panopticon is a prison in which each inmate can be observed at all times, but the inmates can never see those who observe them. The invisible watchman becomes all-seeing. Because I can never know if I'm being observed, I internalize that watchful eye. Foucault writes, "He who is subjected to a field of visibility, and who knows it, assumes responsibility for the constraints of power; he makes them play spontaneously upon himself; he inscribes in himself the power relation in which he simultaneously plays both roles; he becomes the principle of his own subjection" (emphasis mine).

This internalized observation is precisely what The Invisible Man illustrates. Cecilia's abuser wages a psychological war against her. Before long, whether he was in the room or not was immaterial. She believed he was, so—for all practical purposes—he was. She was always under his eye.

My divine chalkboard disciplinarian was a similarly constructed panoptic phantasm. God was not an abiding presence in my young mind, but a distant, moralistic judge. I did not relate with God except when I had transgressed.

Nothing could be further from the picture of God presented in Scripture. God is the one who walks with the man and woman in the garden. God is the one who ate with Abraham. The culmination of the Exodus story is not the 10 commandments—those come at barely the halfway mark—but the construction of the tabernacle and God at last dwelling among God's people.

The Gospel of John puts it most poetically: "The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us." (The Greek word John uses for "made his dwelling" is the same Greek word the translators of the Septuagint used for "tabernacle.") Jesus is Emmanuel, God with us. Jesus is the divine Word become human. John concludes, "No one has ever seen God, but the one and only Son, who is himself God and is in closest relationship with the Father, has made him known."

We can rightly employ Foucault's panoptic theory to critique an "invisible man in the sky" religion that imagines God as a distant, moralistic deity. (Indeed, this is a common application of Foucault's theory, along with Elf on the Shelf.) Faith should not engender the internalized abuse Cecilia experienced in The Invisible Man. A god who watches us from a distance, who cares only that we internalize his watchful eye, is an abusive deity. The God we meet in Scripture is not distant but immanent. Not moralistic, but relational. Not a judge, first and foremost, but a merciful Savior.

Topics: Movies