Culture At Large

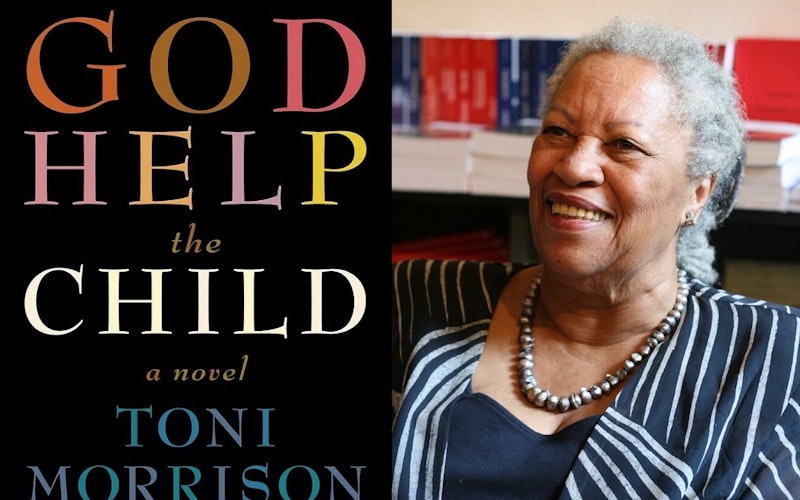

The withering witness of Toni Morrison’s God Help the Child

In a recent Fresh Air interview with Terry Gross, Toni Morrison remarked that her age has brought her to reflect on her life, and in so doing, her regrets. “It's not profound regret,” she said. “It's just a wiping up of tiny little messes that you didn't recognize as mess when they were going on.”

In a way, this illuminates the emotional turmoil that marks the lives of her characters in her latest novel, God Help the Child. But for these characters, it is profound regret that is carried, masked by all the ways that you and I refuse to face our own regrets: counting our successes, casting ourselves as the heroes of our stories, another glass of wine. What Morrison’s latest set of characters regret are things that are not only terrible, but violent in a frighteningly intimate way; my hands often trembled turning the pages. But it is a novel that, like all of Morrison’s work, should be read, its voices and stories functioning as important witnesses to what abuse and neglect in a childhood truly sound like.

The story centers on a woman who calls herself Bride, a name she chose for herself in adulthood. Her mother, whom she calls Sweetness, is deliberately distant, ashamed of her daughter’s deeply black skin, which Sweetness calls “a cross she’ll have to carry.” Bride is scorned by a lover early in the novel and the immediate narrative centers on Bride’s attempts to find this man. But the seam of voices that lace the novel together - those of Sweetness, Bride and Booker (the lover) - bring out other stories, accusations and deeply buried memories that reveal how violent a word or gesture can be for a child. For example, Sweetness refuses to let Bride call her “Mother,” or “Mama,” but chooses “Sweetness” for herself (while chiding her daughter’s choice to change her name from “Lula Ann”). When Bride is called as a witness in a child abuse case, her primary motive for testifying is to please her mother enough so that Sweetness will hold her hand in public. Bride’s cross is not simply the color of her skin, but her mother’s choice to not love her, which feels both plausible and impossibly cruel.

There are many crosses to bear in God Help the Child.

There are many other crosses to bear in God Help the Child. There is not a trigger warning large enough to cover the multitude of abuses described in these pages, especially to children. If you choose to read this book, I must warn you to be prepared. We live in a time when stories about child abuse and sexual exploitation are - thanks to social media and the Internet - incredibly close to us in a way that feels terrifying and overwhelming. But we also live in an incredibly reactive time, one driven by headlines and instant opinion. The stories in God Help the Child force us to pay attention to what abuse does to a person’s heart and soul; they force us to feel the weight of a child’s wails and they bring us to respond to it through mourning, anger and real recognition.

This is what Marc C. Conner describes as the “call and response” of Morrison’s work, which not only reflects the language and culture of Morrison’s “black cosmology,” but situates her readers in such a way as to echo the healing that takes place in a call and response context. We read about the sinister things Bride saw in her apartment stairwell as a child, and we react with horror, but we also keep reading, and in so doing, we are brought more fully into the power of Morrison's language, which Conner describes as a force that “unifies listener and speaker.”

What this unification does, in a powerful way, is bring us into the work of reconciliation, the work of the Cross. The characters’ lives still contain all the terrible things they experienced and remember, but in the events of the novel, they are brought to not only face each other, but to recognize each other as human beings. To be recognized in this way - as a person, an image bearer - is an act of healing, a vital step if reconciliation is ever to take place.

In God Help the Child, we not only listen to the story, but we are invited to see these characters as people. Bride, Sweetness and the others speaking directly to us, asking us to listen. To see what they have seen. Even if your hands tremble, it is an invitation worth taking.

Topics: Culture At Large, Arts & Leisure, Books