Movies

Three Billboards’ Angry Prayer

No one would argue that Golden Globe Best Drama winner Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri lacks passion. The film overflows with spectacular violence, including (but not limited to) bar fighting, fire bombing, and defenestration. Nor would anyone say the movie lacks style. Nearly everyone on screen, from teenagers to barflies to the local constabulary, speaks in writer-director Martin McDonagh’s voice: smart, flashy, and utterly profane.

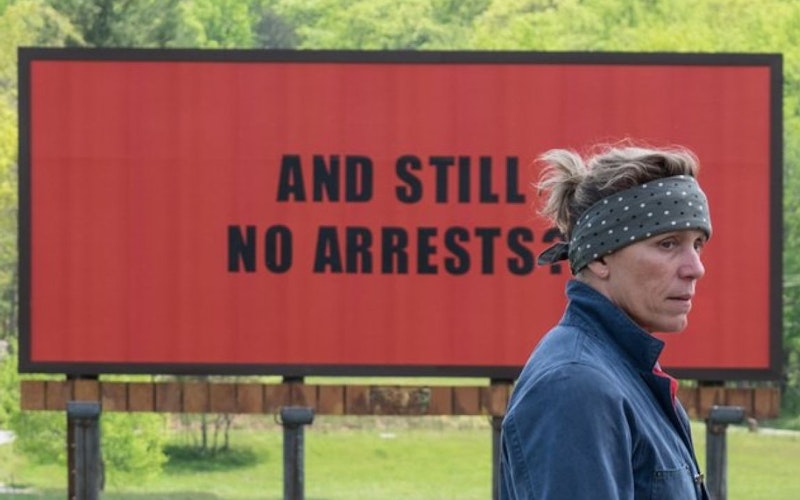

Many have, however, claimed that the film lacks a moral compass, a surprising charge given the movie’s plot: grieving mother Mildred Hayes, played with nuanced intensity by Frances McDormand, rents the titular billboards to criticize the police department’s inability to arrest the man who raped and murdered her daughter.

Even as Three Billboards honors Mildred’s quest, the movie bungles its handling of racism and gives easy redemption arcs to loathsome characters. The movie feels less like a take on timely issues and more like a highly personal and often hopeless prayer, one that demands justice and desires grace, but can’t figure out what those things should look like.

Take the scene in which Mildred’s ex-husband Charlie (John Hawkes) confronts her about the signs. Embodying the town’s resentment toward Mildred for daring to question their beloved Sheriff Willoughby (Woody Harrelson), Charlie explodes and strangles Mildred until his own son threatens him with a knife. McDonagh indulges in the scene’s chaos, drawing close to the actors’ faces to capture the vein pulsing in Charlie’s neck and the fear that seeps into Mildred’s otherwise flinty eyes. But after the knife-point intervention, McDonagh backs into a comfortable medium shot to establish calm, letting the characters chat with one another as if Charlie’s actions meant nothing.

When Charlie, trying to dissuade Mildred, says, “Anger begets a greater anger,” it feels like McDonagh declaring his movie’s thesis, lending reason to the film’s vicious set pieces. But then we learn that the phrase came not from a great philosopher, but from Charlie’s young girlfriend Penelope (Samara Weaving). Who read it on a bookmark. In a book about polio. Or polo. (“Which is the one with the horses?”) What could have been a statement of purpose crumbles with a nihilistic chuckle.

Grace breaks into the story with a force more shocking than the film’s violence.

The joke frustrates, in part, because despite the movie’s excesses Three Billboards manages to find some humanity in its carnage. Grace breaks into the story with a force more shocking than the film’s violence, as when a shouting match halts after the cancer-stricken Willoughby unexpectedly coughs blood onto Mildred’s face. The camera lingers on the actors, emphasizing Willoughby’s shame and Mildred’s rarely seen compassion. Her soft answer to Willoughby’s explanations–“I know, baby”–recalls the caring mother she was before someone killed that part of her.

Another grasp for grace takes place when Mildred encounters a fawn while planting flowers below the billboards. It’s a contrivance, but one that gives Mildred’s strife cosmological perspective. Commenting upon the lack of arrests, Mildred asks, what if “there ain’t no God and the world’s empty and it don’t matter what we do to each other?” She answers herself–“Oh, I hope not”–and, for all its outrageousness, Three Billboards shares this hope. Yet it just can’t envision a God both forgiving and just. Divinity may manifest in a deer in a meadow, but that’s not enough in light of the human suffering on display.

In this way, Three Billboards mirrors some of the most powerful psalms, those in which the poets cry out to a God they cannot understand. “Arise, Lord, in your anger,” David demands in Psalm 7. “Awake, my God; decree justice.” The writer of Psalm 137 outdoes McDonagh’s brutal imagination by declaring “Happy is the one who seizes [Babylonian] infants / and dashes them against the rocks.”

The inclusion of these poems in the Bible reminds us that the Christian walk involves disappointment with God, that the thirst for justice is holy but not always satisfied. The rest of the Bible, however—particularly the life of Jesus—shows us that anger and despair do not define our faith. When we follow Christ by standing with the accused, prosecuting those who exploit the poor, or welcoming the racial outsider, we embody what Three Billboards struggles to imagine. We answer, with hope, the longing for both justice and for grace.

Topics: Movies