Movies

Wes Anderson, Michael Chabon, and Putting the Pieces Back Together

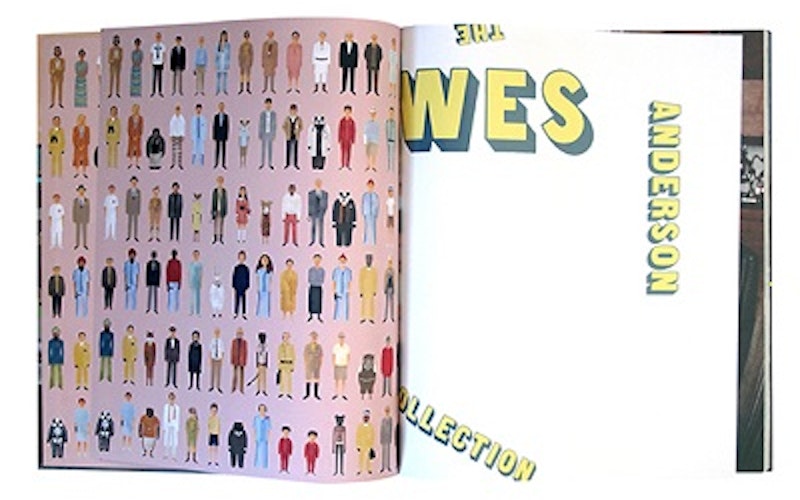

One of the Christmas gifts I received this year was Matt Zoller Seitz's massive book The Wes Anderson Collection, a compilation of essays, interviews and photographs about the director’s work. I dove in to delight in movies like last year’s Moonrise Kingdom, but was surprised to encounter an introductory essay that beautifully described a Christian vision of the world and our place in it.

The piece is by Jewish-American novelist Michael Chabon, whose thoughts are certainly rooted in Judaic tradition. Yet the language of brokenness and restoration he uses has echoes, for me, of Christian thinkers like Abraham Kuyper, whose kingdom vision included “the marred beauty of our sinful condition,” and N.T. Wright, who has described the resurrection as new creation. (In fact, Kuyper’s understanding of common grace is what led me to read Chabon this way in the first place.)

Here is how Chabon begins: “The world is so big, so complicated, so replete with marvels and surprises, that it takes years for most people to begin to notice that it is, also, irretrievably broken. We call this period of research ‘childhood.’”

By adolescence, Chabon writes, the researcher “discovers that the world has been broken for as long as anyone can remember, and struggles to reconcile this fact with the ache of cosmic nostalgia that arises, from time to time, in the researcher’s heart: an intimation of vanished glory, of lost wholeness, a memory of the world unbroken.” Or, as Albert M. Wolters titled his book on the Reformational worldview: Creation Regained.

Chabon goes further, acknowledging that some of us researchers begin to wonder, “Perhaps something might be done about putting the thing back together again.” And here’s where he connects to the films of Anderson. While acknowledging that our restorative attempts “can only be approximations, partial and inaccurate,” Chabon also says: “And yet in that very failure, in their gaps and inaccuracies, they may yet be faithful maps, accurate scale models, of this beautiful and broken world. We call these scale models ‘works of art.’”

Even our greatest artists can only offer “approximations, partial and inaccurate,” of the world as it’s meant to be.

With their precisely arranged frames, rigorously choreographed camera movements and meticulously patterned sets, Anderson’s wry comedies certainly have the aesthetic qualities of scale models - fussy reductions of the larger world that amount to a reconstruction of it. What’s more, their narratives often center on characters fumbling to reclaim a goodness that’s been lost.

And so in Rushmore, precocious 15-year-old Max Fischer (Jason Schwartzman), ashamed of his upbringing, attempts to reinvent himself at the title prep school via a maniacal amount of extracurricular activities (including Bombardment Society Founder). Likewise, in The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, Bill Murray’s title explorer deals with the loss of loved ones by deliriously pursuing a mysterious “jaguar shark,” no matter what the cost. These are therapy comedies, in which absurdly morose characters deal with their sadness in ridiculous ways.

So we have the brokenness Chabon mentions in his essay, but where is the Christology? I think you can sense it in the unexpected epiphanies that arise in each of Anderson’s films. For Max, the unguided flight of a kite releases him from the demands of irrational achievement (never mind that he’s a Kite Flying Society co-founder). For Zissou, encountering the shark in all its awesomeness reveals that there are larger things than vengeance. And in each of these instances, the epiphany is freely given – an act of grace - rather than something these characters earned (especially given the misguided ways they’ve been trying to fix things).

This is what Chabon also recognized: we can’t do it on our own. Even our greatest artists can only offer “approximations, partial and inaccurate,” of the world as it’s meant to be. There is value in these efforts – for Christians, the effort is our way of living in gratitude and participating in the work of the Holy Spirit. But true restoration comes through the accomplishment of Christ. In the cosmic sense, His sacrifice is like my book on Anderson’s work – a gift.

Topics: Movies, Culture At Large, Arts & Leisure, Books, Theology & The Church, Theology