Culture At Large

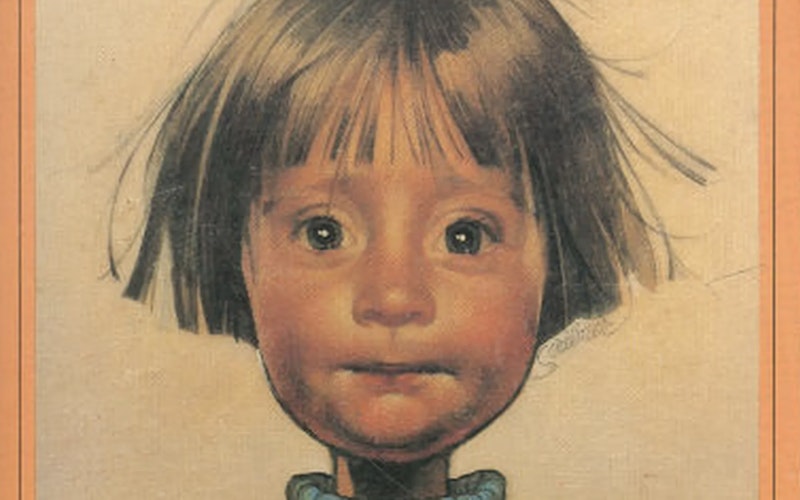

Beverly Cleary, Ramona Quimby, and Growing Up as a Child of God

One of the first chapter books I read on my own was Ramona the Pest, by Beverly Cleary. I spent my summer afternoons sprawled out across my bedroom floor engrossed in her imagined world. Hers was a world that felt as real to me as the very pages flipping through my fingers. It was here that I met, for the first time, a very familiar girl, Ramona Geraldine Quimby. I was in third grade and Ramona felt like me. She was a brash, clumsy, elementary school girl who was both brave and scared. She lacked decorum and was irritated by her siblings, but she loved adventure. In the pages of her life I felt suddenly known.

There are books from childhood whose characters stay forever with you. Decades later, the mere mention of their names instantly takes you back to long afternoons and rainy days spent with friends like Willy Wonka, Kenny Watson, Curious George, Opal Buloni, or Harry Potter. Ramona Quimby is one of these characters for millions of readers. Cleary, her creator, passed away last month at the age of 104. Now her fans have a moment to recall her colorful characters, who represented the stories of a million childhoods.

Beverly Cleary remains one of the top-selling children’s book authors of all time. Born in 1916 into a farming community near McMinnville, Ore., Cleary’s childhood weathered many of the storms known intimately by Depression-era families, including job loss, moving, and watching her parents struggle through hardship and scarcity. Cleary fell in love with literature and eventually achieved her vocational dream of becoming a children’s librarian.

Asked later about the inspiration for her characters, she retold the story of the time a disheveled neighborhood boy with a thirst for adventure approached her at the librarian desk and asked, “Where are the books about kids like us?” At that moment, Cleary is said to have realized most of the stories on the library’s shelves featured buttoned-up, astute, tidy kids who lived with access to ideas or resources that the boy standing before her did not have. She decided to write stories for the scrappy, brazen, ill-equipped, wild kids, those whose spirits could not be stilled and whose creativity would not be tamed.

Cleary went on to write over 40 books that, to date, have sold over 85 million copies. She won the esteemed Newbery Medal, Newberry Honor, the Laura Ingalls Wilder Award, and the National Medal of Art. At a time when children were expected to be compliant and stick to strongly prescribed societal roles, Cleary unleashed characters that refused to fit the mold. Real kids, she called them. They were honest, clumsy, adrenaline-filled characters like Ramona Quimby and Henry Huggins. Her books took kids on the incredible journey of growing up, while addressing some of the social issues facing elementary school children in middle-class America at Cleary’s time: loss and fear, divorce, financial hardship, death, moving, figuring out siblings, and navigating the chaos of school from bullies to finding a table in the lunchroom.

In the pages of Ramona Quimby's life, I felt suddenly known.

The world that Cleary wrote into has dramatically changed, but the affirmation of adventure she instilled in her readers remains relevant today. Cleary’s characters often teetered on the brink of emotional and social risk as they peered into an adult world beyond their understanding. In her work, readers watch children wonder aloud about the complex and scary world of grownups. The grief and triumph her characters experience is honest and relatable. Readers meet them at the edge of childhood where fear, awe, and wonder mingle with the complex issues of real life. Her books take children to a sacred place, where imagination and reality merge to create an experience of feeling known at a time when children are entering the unknown places in their lives.

While Cleary did not specifically write about matters of faith, the spaces she created remind us of the role imagination plays in our own faith journeys. Christians are called to dwell on the mysteries of God. These mysteries, like the ones that Cleary’s child characters explored, take us to the edge of the known and remind us that we are known by God as we dare to engage with the hardships of our world. We are at once living in a tangible reality while also existing on the cusp of the unknown work of God. We teeter daily on the edge of known joys and sorrows as they meet with the mysterious God who holds it all in place. We dwell in a space that, as Paul said, “we only know in part,” the “already but not yet.” We are at once slogging through our days in the lunchrooms and classrooms of our lives, while at the same time standing on the edge of redemption and the glory of God. Stories are often how we make it through these spaces; it is why Jesus harnessed the imaginative power of story throughout his ministry.

Reading Cleary as an adult, we’re reminded that we never truly grow up. Sure, we mature and learn how to behave at a cocktail party, but our souls are forever called to the humble posture of following God into the unknown. Behind the uniforms and masks of our adulting days God calls us to push against the limits of our earthly lives. Where does fear turn into trust? Where does chaos become peace? Where does anger become reconciliation? God calls us to explore these divine spaces and dwell in them much like a child adventures through the unknowns in their life.

One of the great gifts of God is the creative process that authors like Cleary employ to bring us to new places of discomfort, peace, and self-awareness, and to offer reminders of how to live as children of God. May stories like these continue to teach people how to find the edge of themselves and follow God into the unknown mysteries of God’s heart.

Topics: Culture At Large