Movies

BlacKkKlansman’s Less Obvious Villain

Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman contains a powerful message for a Church that seems continually tempted to make a god in its own image.

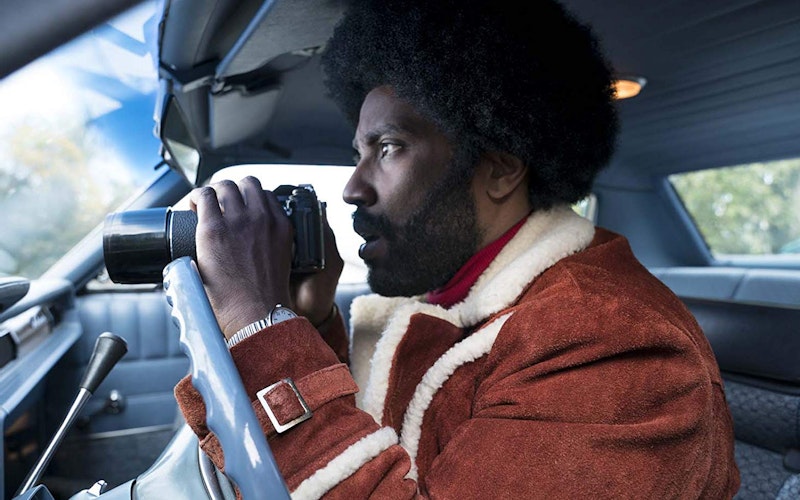

Based on a true story, BlacKkKlansman follows African-American police officer Ron Stallworth (John David Washington), who led a 1979 investigation of a Colorado chapter of the Ku Klux Klan. It is easy for most viewers to see the idolatry of the Klansmen, who claim their white supremacy is supported by the Bible. The film begins with an obvious expression of this hate: a propaganda speech delivered directly to the camera by Dr. Kennebrew Beauregard (Alec Baldwin), who lectures on the harm being done to America by Martin Luther King and those of Jewish heritage. The black-and-white imagery at once demonstrates the age of these racist notions and their longevity in the American psyche. When Beauregard forgets some of his lines, a woman offscreen feeds them to him—one of a few instances in the film where Lee, as director, demonstrates the active participation of white women in white supremacy.

Beauregard directly points to the Bible to justify his racist words. Later, the Grand Wizard of the KKK, David Duke (Topher Grace), prays for God to “give us true white men.” Over and over again these men and the Klan members use Christianity as a justification for their racial hatred and bigotry. It is a clear disavowal of the Bible’s teachings on the imago dei, the doctrine that all people are made in the image of God.

Aside from these villains, there is another character worth considering: Chief Bridges (Robert John Burke), Stallworth’s superior. He officially tolerates Stallworth’s presence, but initially only assigns him clerical duties. When Duke comes to town, Bridges arranges for a security detail to protect him. But when civil rights leader Kwame Ture (Corey Hawkins) visits a nearby college campus, Bridges targets him as a criminal. Chief Bridges may not burn any crosses, but in his other actions, he too perpetuates the image of the white man as the pinnacle of creation, thereby ignoring what Scripture says about the imago dei. While interviewing Stallworth for his job, which would make him the first African-American police office in Colorado Springs, Bridges asks Stallworth how he would respond if another officer called him a racial slur. The assumption is that there are cops on the Colorado Springs police force who are racists. But rather than call out their racism, Bridges puts the onus on Stallworth to control his reaction to it.

It would be easy for most Christians to quickly shake their heads and call out the bigotry of the Klan for what it is—hypocrisy and heresy. More difficult is the self-examination of the ways we, like Bridges, might act as if Scripture has nothing to say about our own complicity in systems that reinforce white racial superiority. We have distilled the gospel into only right beliefs, setting aside expectations of right actions. In doing so, we have committed ourselves—to quote Martin Luther King— to an “otherworldly religion which made a strange distinction between body and soul…”

Chief Bridges may not burn any crosses, but in his other actions, he too perpetuates white supremacy.

This tendency is not new to the church or Christianity, as early Christians often struggled to align their beliefs about God with their actions. Even Peter was not immune to racist behavior. After regularly eating with Gentile Christians in Antioch, he suddenly withdrew from them when an objecting group of Jews arrived. When Paul learned of this, he challenged Peter for preaching a gospel that reconciles Jews and Gentiles, while living in a way that created division and led others astray. Paul called out bigotry even when it meant opposing someone as revered as Peter, declaring that he was “not acting in line with the truth of the gospel.” Paul was concerned not just with people’s souls, but with their bodies. He understood that false actions can serve as false teaching.

Today, many Christians understand and acknowledge that white supremacy is inconsistent with the gospel. But do their actions—or the actions they permit—give evidence of this understanding? When the gospel is divorced from its ethical implications, we deny its true power with our conduct.

BlacKkKlansman reminds us that white supremacy continues to use Christianity as a tool of hate. The film makes the link from Beauregard’s “old rhetoric” with the current activities of white nationalist groups by ending with actual footage from the 2017 Charlottesville rally, which resulted in violence and death. Where is the Church’s voice in response? Often those Christians who do speak out are dismissed or demonized by other believers. If the Church remains silent and allows this heresy to go unchecked in the pews and around the water cooler, we signal that not only does the gospel not speak to this area of life, but that even if it did, we have no interest in living it out.

We cannot claim to honor the image of God in our neighbors while explicitly or implicitly propagating white supremacy. We must, like Paul, oppose this evil not just with our words, but in our actions. Following Paul’s advice to the Corinthians, let us demolish every stronghold—including heretical notions of national, racial, and ethnic superiority—that sets itself against the word of God. We demolish strongholds not by ignoring them, but by opposing them in love, with grace and truth.

Topics: Movies