Movies

Martin Luther at the Movies

The weight of five centuries has a way of flattening out certain historical events in the popular imagination. The Reformation tends to suffer this fate, with the doctrinal arguments at its center giving it a patina of high-church stuffiness. For this reason, it can be easy to overlook how readily the story of the Reformation, and particularly Martin Luther’s role in instigating it, lends itself to the Hollywood treatment.

For the screenwriter looking for a nice, strong story structure, Luther’s life delivers the goods. It features an underdog hero, passionately devoted to a cause but privately plagued with doubts; a monolithic establishment, its corruption exceeded only by its power; and dramatic face-to-face confrontations, complete with cue-the-applause speeches. To date, five feature-film retellings of Luther’s life have been made, and all of them lean on these elements to some extent.

So which ones are most worth your time? Here is a guide to the four Luther movies currently available in some form for home viewing. (Unfortunately, the original cinematic retelling of the Reformation, Hans Kyser’s 1928 silent film Luther, was unavailable, but a trailer advertising a November 2017 DVD release is online for the curious.) In the spirit of the Reformation, the individual is at liberty to exercise personal conscience as to which ones he or she seeks out.

Martin Luther (1953)

Luther’s initial foray into sound cinema met with success right out of the gate: The New York Times’ Bosley Crowther gave it an appreciative review and it was nominated for a handful of awards, including two Oscars. Luther is played by Niall MacGinnis, whose stocky frame and formidable stare make for a fitting representation of the pugnacious theologian.

Director Irving Pichel and his screenwriters establish their film’s historical accuracy with an opening title that touts their “careful research.” Unfortunately, this cautious, scrupulous approach is ultimately to blame for how inert the final product is. Let the viewer understand: Pichel respects his subject. To that end, he fills his film with voiceover instructing the audience exactly what to think of the action onscreen. (“God the angry judge … failed to bring peace to his weary soul,” the narrator says over a shot of an obviously anguished Luther.)

The result is a film woefully devoid of complexity—Luther is a Patrick Henry–style champion of the common man; the Catholic clergy are venal money-grubbers; and there’s not much more to say than that. Pichel makes some vague attempts to explore the violent consequences of Luther’s religious revolution, but he ensures that Luther himself floats above the fray, borne aloft by the strains of “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” that open and close the film.

Luther (1974)

Written in 1961, John Osborne’s stage play Luther became the definitive dramatic adaptation of the reformer’s story for some time. The definitive cinematic version of the play came out in 1974 with the great Stacy Keach in the title role. Osborne’s play evinces a rather ambivalent perspective on Luther, which director Guy Green underscores onscreen. The 1974 film places special emphasis on a character known as “the Knight” (Julian Glover), a character who serves as both a narrator and a jaundiced interlocutor of Luther himself. In stark contrast to the benign narrator of Irving Pichel’s Martin Luther, the Knight introduces us to Luther by smearing Luther’s vestments with the blood of a slain peasant.

Pryce's Luther is here to chew bubblegum and promulgate radical theology, and he’s all out of bubblegum.

It’s a sharp beginning that isn’t quite matched by the rest of the film, which—like so many play-to-movie adaptations—feels artificial and slightly claustrophobic. Still, its characterization of Luther, in tandem with Keach’s performance, is provocative. Keach keeps his American accent while everyone else speaks in the nonspecific British cadences meant to signify “European” to American audiences, which has the effect of singling out Luther from the crowd. He feels like a man ahead of his time. He’s also portrayed as full of contradictions: a holy man with a flair for the scatological; a celebrator of God’s grace who is tormented by guilt; and a populist who sides with the nobility during the peasant revolt of 1525. To the extent that Keach’s Luther is a hero, he’s a profoundly complicated one.

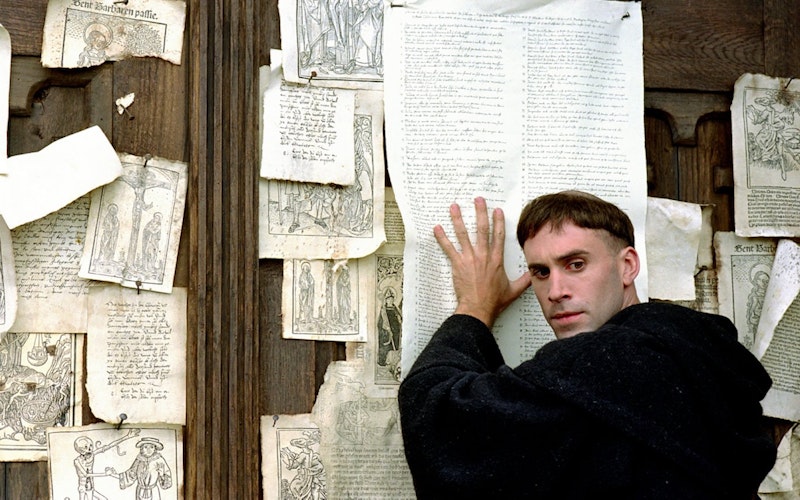

Martin Luther: Heretic (1983)

Director Norman Stone’s version of Luther’s story, made for broadcast on the BBC, wastes no time: the first shot is a close-up of flames, with a character addressing Luther in voiceover as a “child of Satan.” Even the title seems calculated for maximal impact. This Luther is here to chew bubblegum and promulgate radical theology, and he’s all out of bubblegum.

Sporting the tonsure this time around is Jonathan Pryce, whose protuberant eyes and prominent brow are well-suited to the role of a monk-turned-iconoclast. It’s this reckless-prophet quality that made his portrayal of the High Sparrow on Game of Thrones so compelling, and he is very good here as well, portraying Luther’s inner conflicts and outward vehemence with equal ease.

The film surrounding him is somewhat less compelling, thanks mostly to the limitations of 1980s television. Stone and his writer, William Nicholson, are obliged to pare down the conflict to its bare essentials, which makes for some oversimplification and rushed pacing. Based on this version of events, viewers who are unfamiliar with the details of Luther’s role in the Reformation might be excused for thinking that Johann Eck was some sort of Javert figure for Luther. Meanwhile, the film keeps a narrow focus on Luther himself, to the exclusion of some of the broader implications of the Reformation, in Germany and abroad.

Luther (2003)

The most recent adaptation of Martin Luther’s story is a good example of the pitfalls of the biopic as star vehicle. The star in this case is Joseph Fiennes, only five years past his Shakespeare in Love days. In this version, directed by Eric Till, Luther is not only a courageous theologian and writer but also a handsome, soft-hearted hero who is even more prone to grand gestures than the grandiose Luther was in real life. It’s not enough that Fiennes’ reformer questions traditional Catholic teachings on suicide; he must also personally cut down the body of a man who hanged himself and dig a grave in the churchyard by hand.

Would Fiennes have accepted the role if the script had included more dialogue about Martin Luther’s bowels, as the 1974 film does? Who can say, but the extent to which this version puts a glossy spin on the story is difficult to ignore. Till and his screenwriters simply can’t resist sanding down some edges that might have been better left rough. The real Luther possibly engaged in some embellishment with his personal account of the Diet of Worms, but even he didn’t go so far as to write himself a standing ovation after his climactic announcement of “Here I stand; I can do no other.”

There is a lot to like about this version, though—it’s easily the most cinematically dynamic of the four films, and the supporting cast is strong. As the most purely entertaining Luther movie, it goes down smoothly. One has to wonder, though, whether “going down smoothly” is the best approach to subjects as multifaceted and thorny as Luther and the Reformation.

Editor's note: For further Reformation coverage from our partner programs at ReFrame Media, check out Family Fire's article on "Five Blessings from the Reformation;" Today's Reformation-focused month of devotionals; and Groundwork’s podcast series Salvation: Five Insights from the Reformation.

Topics: Movies, Culture At Large, Arts & Leisure