Movies

Traversing towers of Babel

When Philippe Petit strung a wire between the Twin Towers on Aug. 7, 1974, and walked across it some 1,300 feet above the ground, two questions immediately followed: How? Why?

The Walk, a dramatization of Petit’s feat from director Robert Zemeckis (Forrest Gump), ably answers the first question, with the help of IMAX and 3-D technology. (Acrophobiacs should stay away.) But the answer to the second question remains a mystery. Not even Petit himself, in the 2008 documentary Man on Wire, offers an explanation. Describing himself as “a poet conquering beautiful stages” is about as close as he gets.

This is the enduring allure of Petit’s performance. We can’t really wrap our minds around it. Even Petit, in Man on Wire, admits: “It’s clearly … out of human scale.” Yet perhaps a certain understanding might come if we take Petit’s lead and view his walk not as a stunt, but as a work of art.

In Culture Making: Recovering Our Creative Calling, Andy Crouch spends some time tracing the trajectory of human culture in the Bible. For Crouch, the nadir of culture is represented by a place somewhat similar to the World Trade Center: Babel. A feat of technology (“mortar, well-dried bricks and sophisticated architecture,” as described by Crouch), the Tower of Babel is “a massive declaration of independence from God: a defiantly human effort to deal with the world in its wonder and terror – and to put distance between humans and God in all his wonder and terror.”

The enduring allure of Petit’s performance is that we can’t wrap our minds around it.

Crouch’s book goes on to explore the ways we can turn our culture-making impulses back toward honoring God (as Adam and Eve did while cultivating the Garden of Eden) instead of ourselves. Both The Walk and Man on Wire made me wonder: where on this continuum of culture-making might the feat of Petit stand? Was his walk – which took place between two modern towers of Babel – a work of cultural reclamation? Or was it a brazen act of hubris? Was Petit an Icarus whose wings held firm?

For all its preparation and calculation, Petit’s performance also involved a certain amount of surrender. In The Walk (where Petit is played by a rambunctious Joseph Gordon-Levitt), he makes this observation just before entering the Twin Towers: “My life is no longer in my command.” It’s an attitude similar to that of Christian wire walker Nik Wallenda, who crossed a canyon in 2013 as his prayers were captured by microphone for a live audience. TC’s Kristy Quist wrote about that event with some skepticism, and I’ll admit my default posture is similar. But The Walk made me consider that perhaps a sort of transcendence is part of the equation.

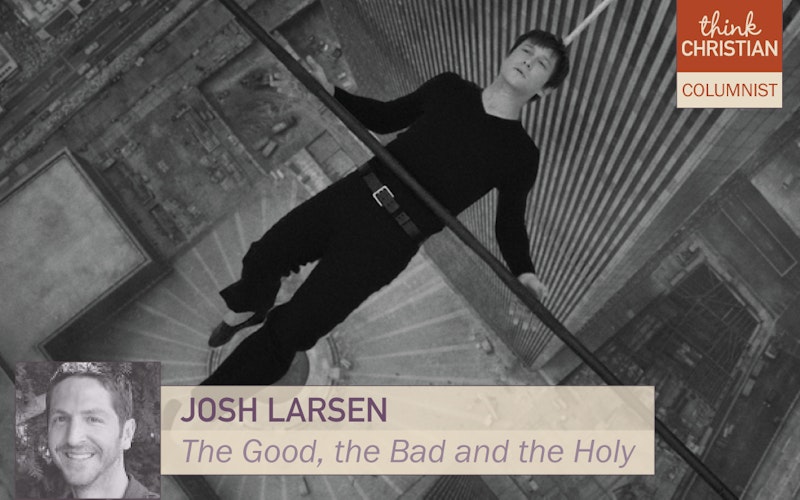

In Man on Wire, Petit says this of his time suspended between the towers: “There was peace and immensity and in the middle of all this madness I suddenly had hope and joy.” The feat of The Walk is the way it captures this in cinematic terms. As Petit takes his first step, a fog drifts across the frame, obscuring everything but the wire itself. When the fog clears and the camera follows him out into the air, there is at once clarity to each step and wooziness to the open space that surrounds him. And when Petit lies down on the wire, staring into the void above (which he has decidedly not conquered), it’s a posture of peace, of gratitude and possibly even devotion.

In the end, Petit’s act of culture-making was so mysterious that it doesn’t seem helpful to ask "why?" or to neatly categorize it with terms like “crazy” or “daring” or “hubristic.” Instead, let’s go with a word that allows for mystery. Let’s just say what Petit did was miraculous.

Topics: Movies, Culture At Large, Arts & Leisure